the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Static-gradient NMR imaging for depth-resolved molecular diffusion in amorphous regions in semicrystalline poly(tetrafluoroethylene) film

Natsuki Kawabata

Teruo Kanki

Understanding spatially heterogeneous molecular diffusion in semicrystalline polymers is critical for elucidating interfacial dynamics in soft materials. This study employs static-gradient nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging to capture the depth-resolved translational motion of polymer chains in a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) film. By focusing on spin–spin relaxation behavior in amorphous regions near crystalline lamellae, we identify multiple diffusion regimes consistent with Bloch–Torrey analysis. The results reveal that molecular mobility at the substrate interface of PTFE film, immobilized on a glass substrate using epoxy resin, is significantly constrained, likely due to interfacial pinning, while the air-side surface shows signs of enhanced mobility. Our findings highlight the utility of static-gradient field NMR for probing nanoscale dynamical heterogeneity in semicrystalline systems.

- Article

(3172 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Heterogeneity in the dynamical behavior of polymer films – manifested as distinct molecular dynamics at the air-facing surface within the bulk and at the substrate interface – profoundly influences their physical properties, particularly dynamic viscoelasticity (Keddie et al., 1994; De Gennes, 2000; Fukao and Miyamoto, 2000; Merabia et al., 2004; Roth and Dutcher, 2005; Fakhraai and Forrest, 2008; Ediger and Forrest, 2014; Inoue and Kanaya, 2012). Over the past few decades, considerable efforts have been devoted to clarifying how interfacial and surface regions contribute to phenomena such as the glass transition, highlighting the critical role of site-specific molecular mobility. To further unravel these complex dynamics, analytical techniques that can provide spatially resolved information about molecular motion in polymer thin films are indispensable.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers a powerful and noninvasive means of probing molecular structure and dynamics across a broad range of materials (Westbrook and Talbot, 2018; Blumich, 2000; Blümich et al., 2008; Blümich, 2019). Among NMR-based approaches, pulsed gradient spin-echo (PGSE) methods have been widely adopted because they enable both high-resolution spectroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Callaghan, 2011; Price, 1997; Mansfield et al., 1976; Mansfield, 1977). Nevertheless, while PGSE methods are well suited for liquid systems, the gradient strengths achievable in typical setups are often insufficient to study solid-state specimens or to capture diffusion processes with extremely small diffusion coefficients (Kimmich et al., 1991; Chang et al., 1994, 1996; Ailion, 1999). These limitations underscore the need for alternative approaches that are specifically tailored to solid materials.

Furthermore, electrically conductive solid components within the sample can generate substantial eddy currents, potentially degrading the specimen. Because eddy currents distort the NMR signal, it is necessary to wait for an adequate period for their decay prior to acquiring a reliable measurement (Chapman et al., 1957; Gibbs and Johnson, 1991; Price, 1998). In addition, conventional high-frequency NMR systems that rely on superconducting magnets demand extensive operational infrastructure – large-scale facilities, cryogenic cooling, and vacuum environments – which imposes significant financial and logistical burdens. Thus, there remains a pressing need for a simple, cost-effective, and versatile MRI method that can provide spatially resolved information on molecular dynamics in solid systems.

To overcome these challenges, methodologies utilizing static magnetic field gradients (SFGs) have been developed as compelling alternatives (Chang et al., 1994, 1996; Ailion, 1999). While PGSE relies on pulsed gradients, SFG techniques use a continuously imposed gradient. Early implementations typically used fringe fields of electromagnets and were limited by thermal and power constraints, but later studies demonstrated that sufficiently strong gradients can be achieved using superconducting magnets (Kimmich et al., 1991). As a result, SFG-based approaches have enabled quantification of self-diffusion coefficients in solids and have inspired diverse, cost-effective platforms, including the superconducting fringe field (SFF) technique (Kimmich et al., 1991), stray-field imaging (STRAFI) using GARField magnets (Dias et al., 2003), anti-Helmholtz superconducting magnets (Chang et al., 1994, 1996), NMR MOUSE (Eidmann et al., 1996), single-sided NMR systems (Blümich et al., 2008), bulk high-temperature superconducting magnet-based systems (Takahashi et al., 2022), Halbach-array NMR sensors (Raich and Blümler, 2004; Doğan et al., 2009; Tayler and Sakellariou, 2017; Chang et al., 2006), and compact ferromagnet-based MRI systems (Asakawa and Obata, 2012). These developments clearly demonstrate the potential of SFG-based MRI to complement or even replace conventional PGSE approaches, especially for solid materials.

However, another complication arises from the fact that, in many SFG-based NMR systems, the static magnetic field governing resonance conditions and the magnetic field gradient used for imaging or diffusion measurements cannot be independently controlled. This interdependence complicates NMR measurements across different frequencies while maintaining consistent spatial resolution. Nevertheless, spatially resolved measurements of spectral density functions – i.e., local spectral densities – are increasingly in demand, as they enable advanced imaging modalities. Addressing these challenges calls for the development of novel SFG-based MRI methodologies that combine simplicity, tunability, and sensitivity to solid-state molecular motion.

In this context, the present study introduces a novel, nondestructive, and facile molecular dynamics imaging technique. This approach employs a locally generated magnetic field gradient produced from a needle-shaped ferromagnetic material developed in-house. Using this technique, we perform depth-resolved spin–spin relaxation rate (R2) imaging of a polymer film, enabling direct comparison of molecular dynamics at the film surface and near the substrate interface.

In our previous study, we measured variable-frequency spin–lattice relaxation rates (R1) to determine the spectral density function associated with spatially resolved local molecular motion (Kawabata et al., 2024). Although the thicknesses of the surface and interfacial regions estimated from R1 variations were overestimated due to 19F–19F spin diffusion, a clear disparity between the surface/interface and interior of the PTFE film was confirmed. However, the R1 values showed no discernible differences between the air-side surface and the polymer–substrate interface. This result contrasts with the widely reported behavior of conventional glass-forming polymer thin films, where Tg typically decreases at the free surface (Forrest et al., 1996; Forrest and Mattsson, 2000; Mattsson et al., 2000; Dalnoki-Veress et al., 2001; Park and McKenna, 2000) and increases near the substrate interface (Lin et al., 1999; Fryer et al., 2000; Tanaka et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2019). This discrepancy may arise because R1 reflects only rotational (more precisely, reorientational) molecular dynamics and is insensitive to translational diffusion.

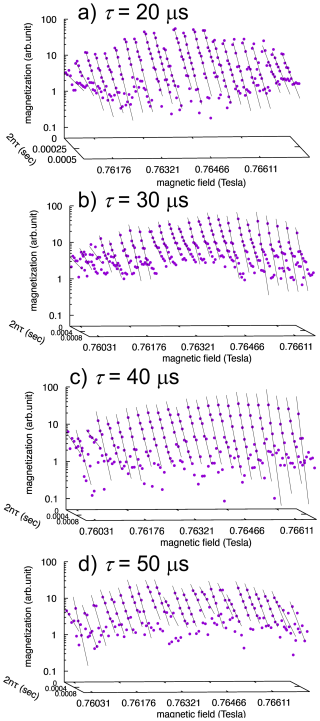

To complement our previous work, we examined the influence of translational diffusion on spin–spin relaxation using an R2 dispersion approach (Yu, 1993) by systematically varying the echo time in the Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) sequence (Carr and Purcell, 1954; Meiboom and Gill, 1958). The CPMG sequence was employed for the MRI measurements, and the dependence of R2 on translational diffusion was examined by varying the half echo time, τ, as follows: depth-resolved one-dimensional imaging was achieved by stepwise modulation of the static magnetic field strength using a normal-conducting electromagnet. The RF intensity for the CPMG method was nominal 50 kHz, which was calibrated using a CPMG pulse sequence under a homogeneous resonant magnetic field only from the electromagnet. At each magnetic field point, 256 signal accumulations were acquired at a resonance frequency of 29.750000 MHz. The decay plots and fitting curves for the CPMG measurements are shown in Appendix A. Furthermore, the influence of the intrinsic R2 on the experimentally obtained R2 was negligibly small (see Appendix B). However, in the R2 dispersion method employed in this study, accurately determining the diffusion coefficient is challenging due to the ambiguous nature of the local magnetic field gradient within the sample. Consequently, it should be emphasized that the diffusion analysis presented here is qualitative in nature. It should be noted that the PTFE sample studied here is a highly crystalline polymer, with a degree of crystallinity of approximately 90 % (Kawabata et al., 2024). In the CPMG spin-echo method used in this study, NMR signals from the crystalline regions are expected to decay rapidly due to strong 19F–19F dipolar interactions, and thus they do not contribute significantly to the observed spin echoes. The detected NMR signals primarily arise from amorphous regions located at the surfaces of crystalline grains. Although these amorphous molecules are in a rubbery state, their diffusion is restricted by surrounding molecules and crystalline domains. Therefore, as discussed later, the diffusion characterized in this study represents motion within compartmentalized and confined amorphous spaces.

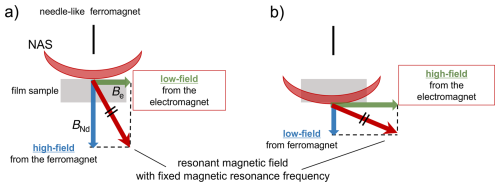

2.1 Principle of depth profiling

The magnetic field gradient experienced by the sample arises from the combined influence of the static magnetic field and its gradient along the thickness of the polymer film. This gradient is induced by a needle-shaped ferromagnetic material and the uniform external static magnetic field generated by the electromagnet. In our one-dimensional MRI approach, we fix the resonance frequency and apply a spatially selective RF pulse with an RF field strength of nominal 50 kHz. This pulse excites nuclear spins only within a narrow slice (the NMR-active slice; NAS), whose spatial position is defined by the static field gradient at the chosen resonance frequency. By incrementally varying the static magnetic field, the effective field gradient experienced by the sample changes, and consequently, the position of the NMR-active slice is shifted along the thickness direction of the film (Fig. 1). This procedure enables one-dimensional imaging along the sample depth without the need for frequency-swept selective excitation or gradient switching during RF irradiation. A similar principle – distance encoding realized by the translation of a spatially selective sensitive volume – has long been employed in well-logging NMR (Hürlimann and Griffin, 2000). Our method shares the same fundamental mechanism: the imaging contrast arises from the interplay between a localized excitation region and its systematic displacement through the sample. This conceptual parallel underscores the validity of our approach and places it within the broader class of one-dimensional imaging methods that rely on spatial selectivity and controlled volume movement.

Within this framework, the spin density or molecular dynamics at a specific location within the sample can be characterized by analyzing the NMR signal arising from the intersection volume between the excited volume and the sample. The morphology of the excited volume, which is shaped by the presence of a needle-shaped ferromagnetic material, is anticipated to adopt a concave geometry, as illustrated in Fig. 1a (Degen et al., 2009; Chao et al., 2004). The excited volume can be displaced vertically by modulating the strength of the external static magnetic field produced by the electromagnet, as shown in Fig. 1a and b. Systematic variation in the external static magnetic field enabled the acquisition of a depth-resolved profile of the sample.

Figure 1In our one-dimensional MRI approach, the resonance frequency was fixed, and a spatially selective RF pulse with an RF field strength of nominal 50 kHz was applied. This pulse excites nuclear spins only within a narrow slice (the NMR-active slice; NAS), whose spatial position is defined by the static field gradient at the chosen resonance frequency. By incrementally varying the static magnetic field, the effective field gradient experienced by the sample changes, and consequently, the position of the NAS is shifted along the thickness direction of the film. The combined effect of the magnetic field generated by the needlelike ferromagnet, BNd, and the static magnetic field from the electromagnet, Be, gives rise to the mechanism of movement of the NMR-active slice.

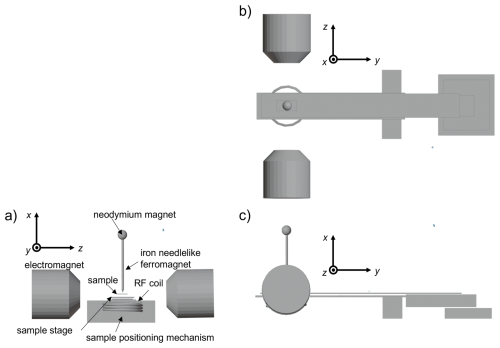

2.2 Experimental setup

The experimental setup for this methodology is illustrated in Fig. 2. A spherical neodymium magnet (8 mm diameter sourced from TRUSCO Nakayama Corporation) and an iron needle (1 mm diameter with a tip diameter of 0.2 mm) were affixed to the aluminum jig. By bringing them in direct contact, the iron needle is magnetized and transformed into a ferromagnetic needle that functions as a localized ferromagnetic material. The needle was positioned between the poles of a water-cooled electromagnet, serving simultaneously as a static magnetic field source and static magnetic field gradient generator. For detailed specifications of the apparatus, refer to our previously published work (Kawabata and Asakawa, 2024; Kawabata et al., 2024).

Figure 2Schematic illustration of an MRI probe. Three-dimensional views from the y axis (a), x axis (b), and z axis (c) are shown. A small spherical neodymium magnet magnetizes the paramagnetic needle, converting it into a needlelike ferromagnet. A two-dimensional mechanical scanning stage is shown (only the function for sample positioning is used in this work, not the scanning function).

3.1 Depth-direction one-dimensional spin–spin relaxation rate imaging of a single layer of polymer film

To investigate the effect of translational molecular diffusion at the film surface and the polymer–glass interface, we performed one-dimensional imaging of the spin–spin relaxation rate (R2) of 19F nuclei along the depth of a 2 mm thick PTFE film immobilized on a glass substrate using epoxy resin. From the blurred image of the sample, which is determined from magnetization intensity, this method achieves spatial resolution of the order of sub-millimeter scale, which enables observation of mesoscopic heterogeneities.

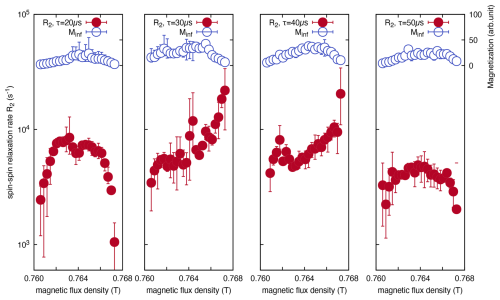

The resulting R2 imaging data are presented in Fig. 3, where Minf represents the NMR signal intensity. In this imaging approach, the horizontal axis corresponds to the static magnetic field strength generated by the electromagnet, with an increasing field strength corresponding to deeper regions within the sample. Thus, the region of lower static magnetic field strength represents the air-facing surface of the film, whereas the region of higher static magnetic field strength corresponds to the interface with the glass substrate. As shown in Fig. 3, no variations in R2 are present near the air-side surface of the film (Be<0.762T) for different τ values. A similar trend was observed in the interior of the film. However, near the glass-side interface of the film (Be>0.766T), complex behavior in R2 emerged. Specifically, as τ increases, R2 initially exhibits an increase (τ=30 µs) before subsequently decreasing for longer τ values (τ=40 µs and τ=50 µs). The contrasting behavior of R2 at the air- and glass-side interfaces of the film could be attributed to different molecular interactions. At the air interface, PTFE molecules behave as free ends owing to the surface energy effects of interactions with adjacent PTFE molecules. Conversely, near the glass substrate interface via epoxy resin, the pinning effect induced by interactions between epoxy resin and PTFE molecules is presumed to constrain translational diffusion, thereby influencing the observed relaxation dynamics.

Figure 3Magnetic field dependence (corresponding to depth dependence) of the T2 relaxation rate (R2), measured using the CPMG method at different echo times for a PTFE film, adhered to a soda-lime glass substrate with epoxy resin. R2 rate showed minimal contrast at the PTFE film surface (Be<0.762T), whereas it displayed remarkable changes at the substrate interface (Be>0.766T).

Based on the experimental findings presented above, we hypothesize that the variation in the dependence of R2 on increasing τ arises from differences in the translational diffusion effects. This is modulated by the distinct interfacial environments of the PTFE film, such as air or the glass substrate.

3.2 Three diffusional regimes and regime transitions

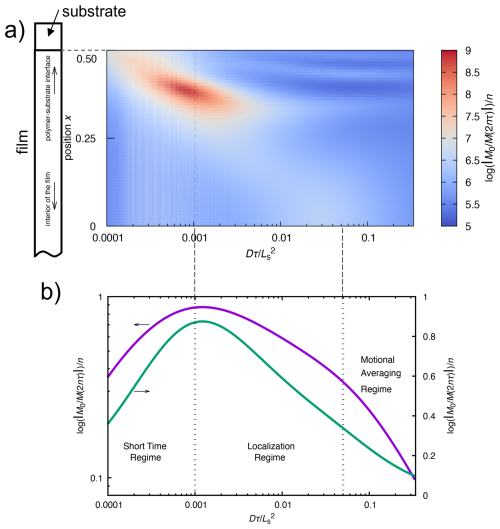

Figure 4a illustrates the results of numerical simulations using the Bloch–Torrey equation (see Appendix C). The variation in diffusion regime with the dimensionless diffusion coefficient ) and position x of the nuclear spin in real space is represented on the xy axes of the plot. The contribution of the relaxation exponent of the spin–spin relaxation rate R2 due to diffusion is depicted along the z axis. When the echo time τ is short, the spins have not yet reached the diffusion barrier and therefore undergo free diffusion. Therefore, spins remain within the short-time regime. Here, the molecule is free to diffuse throughout the space. As molecular diffusion advances and the molecule approaches the diffusion barrier, it transitions into a localization regime where diffusion is constrained by the barrier. As the diffusion continues, the molecule enters the motional averaging regime, undergoing multiple round trips between the diffusion barriers.

In this regime, molecular motion undergoes averaging such that the system appears stationary and diffusion is not observed. Given the difficulty of observing the three-dimensional curve in Fig. 4a, the sum of the magnetization versus position in real space is plotted with respect to in Fig. 4b. The figure shows the presence of three distinct regimes.

Figure 4Simulation of the relaxation exponent of the first echo signal of the CPMG experiment using the Bloch–Torrey equation for the diffusion of nuclear spins in a compartmentalized environment. The contribution of diffusion to the spin–spin relaxation rate R2 is color-coded (a), where the relaxation exponent of the CPMG echo intensity M(2nτ) (for n=1) is plotted as a function of the dimensionless diffusion coefficient (or dimensionless echo time) and position within the sample. The position is defined relative to the midpoint between diffusion barriers of the compartment, with a magnetic field gradient symmetrically distributed about the origin, having the form g(x)=x4. The figure presents data for only half of the compartment. The simulation models a polymer film confined between two substrates in order to apply periodic boundary conditions. In practice, however, only one side of the polymer film adheres to the substrate, while the opposite surface is exposed to air. Thus, the film possesses an asymmetric structure along the depth direction, with one interface in contact with the substrate and the other with air. Consequently, only the results corresponding to the substrate–film interface are displayed. The dimensionless diffusion coefficient is expressed as , where Ls represents the distance between the diffusion barriers of the compartment, D is the diffusion coefficient, and τ is the CPMG echo time. Panel (b) illustrates the total observed magnetization within the compartment as a function of the dimensionless diffusion coefficient, highlighting the three regimes.

3.3 Distinction between surface and interface

Building on the aforementioned observations, we examine the behavior of R2. A consistent trend was observed across all echo times. τ conditions used in the experiment were as follows: R2 was notably smaller on the air-side surface of the PTFE film (Be<0.762T) than in the interior of the film. The observed difference in R2 between the surface and the interior of the film originates from intrinsic variations in the local polymer morphology rather than from differences in diffusion. A reduction in R2 on the air-side surface was observed irrespective of the variation in τ. Results from variable-frequency R1 measurements (Kawabata et al., 2024) indicated that, within the resonant frequency range (29.75 MHz) employed for the R2 measurements, the R1 value near the surface was 1.5–2 orders of magnitude larger than the R1 value of the film. Hence, the contributions of R1 to R2, that is, the effect of the secular term, were considered negligible. Therefore, we hypothesize that a reduction in R2 observed at the film surface can be attributed to differences in the zero-frequency component of the spectral density function, J(ω=0). Based on the established variation in the spectral density of molecular motion near the film surface or substrate interface (Kawabata et al., 2024), PTFE molecules are postulated to exhibit enhanced molecular motion, particularly the reorientational motion at zero or low frequencies below several hundred kilohertz, compared to the bulk of the film. It should again be emphasized that the observed thicknesses of the surface and interfacial regions are significantly greater than the typical values – of the order of several tens of nanometers – commonly reported for surfaces and interfaces in nanometer-scale thin films (Forrest et al., 1996; Forrest and Mattsson, 2000; Mattsson et al., 2000; Dalnoki-Veress et al., 2001; Park and McKenna, 2000; Lin et al., 1999; Fryer et al., 2000; Tanaka et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2019). This discrepancy is attributable to the spin diffusion effect of 19F–19F interactions on R2.

3.3.1 Behavior of the air surface and interior of the polymeric film

We now examine the impact of variations in the echo time τ on the air-side surface and the interior of the PTFE film. The results demonstrate that the value of R2 remains largely unchanged even when the echo time τ gradually increases. By comparing this behavior with Fig. 4a, the system is in the localization regime, where changes in τ exert a minimal influence on R2. This suggests that the air-side surface acts as a free end, where the dynamics of individual polymer chains are not entirely random, and that these chains function as a diffusion barrier in the direction normal to the film surface because of their interactions with adjacent polymer chains. Moreover, since the R2 value of the PTFE molecules within the film was independent of the variations in τ, the behavior observed on the film surface can be attributed to the film interior. However, within the film, unlike the one-dimensional diffusion barrier perpendicular to the film surface, localization is presumed to arise from collisions with the three-dimensional barriers formed by the surrounding PTFE molecules.

3.3.2 Behavior of the interface between the polymeric film and the substrate

We now focus on the region near the interface between the PTFE film and the glass substrate via epoxy resin. Near the glass-side interface of the PTFE film (Be>0.766T), R2 exhibits notable variation when τ shifts from 20 to 30 µs. However, as τ reaches 40 µs, the value of R2 begins to decline, and by the time τ reaches 50 µs, R2 decreases precipitously. The observed behavior can be attributed to a transition of the observable from the localization regime to the averaging regime with increasing τ.

3.4 Pinning effect at interface

The diffusion behavior of PTFE molecules near the PTFE film interface differed from that in the film interior or near the film surface, owing to the influence of the epoxy resin. This disparity is due to employing the same sample for all the experiments conducted at 298 K, under the assumption that the diffusion coefficient D remains constant under isothermal conditions. Here, D represents the diffusion coefficient as the statistical average of random motion, akin to Brownian motion. In other words, D corresponds to the diffusion coefficient in the Fokker–Planck equation, which is used when the Langevin equation for a single molecule that accounts for random forces due to thermal fluctuations at a given temperature is extended to a molecular ensemble. In the case that D and τ are constants, in (= ), only Lg denotes a variable. Here, the distance between diffusion barriers Ls is replaced by the effective diffusion barrier distance, which is denoted as the spin packet length Lg (see Appendix D for more details).

Specifically, when τ was set to 20 µs, a regime transition was observed in the depth direction of the polymer film, as depicted in the plot for τ=20 µs in Fig. 3. This transition occurred between the localization and motional averaging regimes. Since D and τ are constants and the variations in are attributed to the changes in Lg, the transition is triggered by a reduction in the spin packet length Lg.

Near the substrate interface, significant changes in τ cause R2 to transition from increasing to decreasing. Thus, a reduction in Lg and an increase in τ lead to an increase in , which results in regime transition. Here, we explored this phenomenon. On the air-side surface of the PTFE film, despite the variations in τ during CPMG measurements, the value of R2 exhibited a minimal change, indicating that the molecules on the air-side surface of the film were in the localization regime. In other words, the PTFE molecules on the air-side surface exhibited behavior consistent with restricted diffusion. However, when considered in conjunction with the experimental results for R1 reported previously (Kawabata et al., 2024), the effect of translational diffusion was found to be equivalent to that observed on the air-side surface and in the interior of the PTFE film, with the observed difference in R2 arising from variations in the spectral density function, J(ω=0), which is attributed to reorientational motion. This conclusion differs from the well-known results of translational diffusion of glassy polymers near the air-side surface, as revealed by fluorescence lifetime experiments and coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations (Tanaka et al., 2009), in which a polymeric thin film shows a decrease in the glass transition temperature at the surface. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fact that our R2 dispersion experiments were carried out under rubbery-state conditions, at temperatures significantly higher than Tg.

On the other hand, the observed relationship for the glass–substrate interface can be explained as follows: the spin packet length Lg diminishes near the glass–substrate interface compared with that within the bulk of the film. There are two potential explanations for the reduction in Lg. The first explanation involves an increase in the strength of the local magnetic field gradient owing to the contrast in magnetic susceptibility at the interface between the PTFE film and epoxy resin on the glass substrate. However, in this case, the effect of diffusion on R2 increases monotonically. This is because when the magnetic field gradient strength is simply enhanced, the transition point between the localization regime and the motional averaging regime shifts to a larger , making it challenging to traverse the transition point by merely increasing τ. In this study, the transition from an increase to a decrease in R2 owing to an increase in τ, that is, a regime transition, was observed, suggesting that the contribution from changes in the local magnetic field gradient is relatively minor compared with the contribution from the increase in τ. That is, a reduction in Lg can be attributed to the second potential explanation, the diffusion of PTFE molecules. We speculate that the most likely mechanism for this phenomenon is the pinning effect of PTFE chains at the interface between the PTFE film and glass substrate. This pinning effect led to a reduction in Ls, which subsequently results in a decrease in Lg.

To provide a unified interpretation of this phenomenon, we applied the Bloch–Torrey equation, which integrates the effects of diffusion into the Bloch equation and the CPMG spin-echo experiment, followed by analyzing the diffusion regime transition in one-dimensional MRI. As illustrated in Fig. 4a), compared with the interior of the film, which is distant from the diffusion barrier, the regime transition occurs at a smaller near the diffusion barrier where the magnetic field gradient is substantial.

As described above, NMR R2 imaging of the depth profile of a polymer film, utilizing a static magnetic field gradient generated by a needle-shaped ferromagnetic material, revealed distinct variations in diffusion behavior near the air-side surface of a PTFE polymer film compared to the film interior and substrate-side interface. The methodology developed in this study offers a novel approach for imaging heterogeneous materials and dynamic imaging of molecular processes.

For CPMG measurements, the plots of decay data for each excited volume as a function of 2nτ are shown in Fig. 1. Here, we discuss the determination of R2. The one-dimensional images reconstructed from the acquired signal intensities appear as blurred images, rather than reflecting the true rectangular geometry of the sample, resulting in broadened profiles. These blurred images arise from the convolution of the true sample geometry with the point spread function, which itself is determined by the spatial dependence of the magnetic field strength within the sample. Consequently, the data points in adjacent regions of the image do not originate from spatially independent excited volumes but instead represent correlated points. While this characteristic constitutes a limitation of the present method, it also suggests the possibility that, in the future, inverse problem approaches to convolution – such as the Landweber iteration method (Degen et al., 2009; Chao et al., 2004; Landweber, 1951; Spencer and Bi, 2020) – may enable imaging with significantly enhanced spatial resolution.

Distinguishing between the intrinsic R2 and the contribution arising from diffusion is crucial for accurately evaluating the influence of diffusion on R2. However, when the intrinsic R2 lies within the short-time regime, namely the free-diffusion regime, it can be determined by extrapolating the R2 vs. τ plot to τ→0. Similarly, when the diffusion process resides in the motional averaging regime, the intrinsic R2 can also be estimated. In contrast to the short-time regime, however, extrapolation concerning τ is not possible; instead, if the plot exhibits a value asymptotically approached with increasing τ, this value can be regarded as the intrinsic R2. By contrast, when the system falls into the localization regime, these methods cannot be applied. Furthermore, as demonstrated in the present study, in cases where regime transitions occur with variations in τ, determination of the intrinsic R2 may not be straightforward. Therefore, we attempted to estimate the intrinsic R2 from the τ dependence of R2 in the motional averaging regime. However, since the τ dependence did not exhibit a clear asymptotic value, the intrinsic R2 could not be determined. Nevertheless, from the peak-like feature observed in the τ dependence of R2 near the interface with the substrate, it can be inferred that R2 already decreases to approximately 102 s−1 or less at an echo time of τ=100 µs. This suggests that the maximum intrinsic R2 is of the order of 102 s−1 and is likely smaller.

According to the Solomon–Bloembergen theory (Solomon, 1955), using a correlation time of 1 µs estimated from R1 and the second moment of the 19F–19F magnetic dipolar coupling, kHz)2 = 5.27 × 1010 s−2, the relaxation rate can be estimated as s−1. This value exceeds the experimentally obtained R2, indicating that employing the correlation time corresponding to crystalline domains is not appropriate. In the CPMG method, signals from crystalline regions are attenuated by rapid R2 relaxation during the echo intervals; therefore, the observed signals in this study are considered to originate solely from the amorphous regions. By adopting the reported correlation time of s for the amorphous phase, R2 is estimated as s−1. Assuming that the intrinsic R2 contributes within the range of 10−3–102 s−1 to the experimentally observed R2, this contribution is negligibly small. Consequently, in this work, the experimentally obtained R2 values were plotted without subtracting the intrinsic R2 component.

Magnetization decay in a spin-echo experiment subjected to a static magnetic field gradient can be simulated by numerically solving the Bloch–Torrey equation (Torrey, 1956; Axelrod and Sen, 2001; Asakawa et al., 2005; Asakawa and Obata, 2012). This section presents a solution to the Bloch–Torrey equation within a compartmentalized diffusion environment. In this context, the compartments emulate the cage effect imposed by the surrounding molecular segments of the polymer chains, a phenomenon frequently considered in the study of glass transition behavior (Doliwa and Heuer, 1998) or amorphous polymer chains between crystalline regions. Although the surface morphology of semicrystalline PTFE is not yet fully established, a study on AFM has reported a multiscale hierarchical surface structure (Korolkov, 2021). At the ∼100 µm scale, large domains (∼20 µm) interconnected by rope-like features are observed. At higher spatial resolution (∼100 nm), highly oriented crystalline regions, presumably lamellae of the order of ∼100 nm, are separated by amorphous regions of several tens of nanometers. In our study, the characteristic distance between diffusion barriers, Ls, is therefore presumed to be of the order of several tens of nanometers. However, our technique does not allow direct determination of Ls or the effective spin packet length Lg because the effective magnetic field gradient contains a significant but unknown local component arising from the intrinsic magnetic-susceptibility variations in the PTFE sample.

The Bloch–Torrey equation is given by

where the tilde denotes the dimensionless parameters, allowing the problem to be treated in a generalized framework. The contributions of the longitudinal relaxation (R1) and intrinsic transverse relaxation (R2) in the original Bloch–Torrey equation were neglected in this calculation. Although these effects must be accounted for in practical applications, it is found that the effects are negligible in our case.

The dimensionless diffusion coefficient , the dimensionless gyromagnetic ratio , and the dimensionless one-dimensional coordinates are defined as

where D, Ls, γ, and x represent the diffusion coefficient, the characteristic length of the aforementioned compartment, the gyromagnetic ratio of a noticed nuclear spin, and the spatial position of the nucleus within the molecule, respectively.

Because the temporal sequence during echo time τ is irrelevant in transverse relaxation measurements, τ can be considered to be a single computational step. The time evolution operator for the spin-echo experiment over echo time τ is given by

Thus, the propagator of a two-pulse Hahn echo (Hahn, 1950) can be expressed as follows:

Similarly, the propagator of the second echo in the CPMG sequence is given by

Extending this to the nth echo in the CPMG sequence, that is, the propagator, gives

Consequently, the kth Fourier component of the magnetization at time t=2nτ is computed as follows:

Initial magnetization M(k,0) is determined using the following initial conditions ):

The Fourier component M(k,0) of the initial magnetization can be obtained using the inverse Fourier transform of . For instance, for a homogeneous spin density, where (constant), all the Fourier components vanish, except for k=0 because the inverse Fourier transform yields a delta function. Substituting the obtained M(k,0) into Eq. (C9), the kth magnetization, M(k,t) at time t(=2nτ), can be determined. Finally, the magnetization in real space M(x,t) is obtained using the inverse spatial Fourier transform of M(k,t):

In panel (a) of Fig. 4 in the main text, it is not straightforward to clearly identify the three diffusion regimes; therefore, in panel (b), we presented the vertical axis as the spatial summation of magnetization over all positions x. By stating that the results were “mapped to real space”, we meant that, after solving the Bloch–Torrey equation in Fourier space, we applied the inverse Fourier transform to recover M(x,t) in real space. The plot in panel (b) of Fig. 4 in the main text further shows as a function of the dimensionless echo time, representing the total magnetization integrated over all positions. The purpose of panel (b) was thus to make the visualization of the three diffusion regimes more accessible. Panel (a), on the other hand, demonstrates that in one-dimensional imaging, the echo times at which regime transitions occur differ between regions near the substrate interface and those deeper within the film.

A Fourier transform approach was employed to solve the Bloch–Torrey equation, which implicitly imposes periodic boundary conditions. In the case of a PTFE film sandwiched between two substrates, the interactions at both film surfaces with the substrates create a symmetric structure along the film thickness, making the direct application of periodic boundary conditions appropriate. However, in the present study, the polymer film exhibits an asymmetric structure, with one surface exposed to air and the other interfacing with the substrate. Therefore, we used only the simulation results corresponding to the half-depth of the compartment adjacent to the substrate, as shown in Fig. 4a in the main text.

Here, we elucidate the concept of spin packet length, Lg (Le Doussal and Sen, 1992). The spin packet length represents the characteristic length scale associated with molecular diffusion. As mentioned previously, the distance between the diffusion barriers, which defines the spatial range over which molecules can diffuse, is denoted by Ls. In NMR measurements, Ls refers to the spatial extent to which PTFE molecules can move. However, in practical NMR relaxation measurements, the spatial region contributing to the magnetization is restricted, and not all nuclear spins within the sample are detected by NMR. In other words, in regions exposed to a strong magnetic field gradient, where magnetization relaxation is completed during the echo time before the signal is observed, such as near the diffusion barrier, the magnetization remains undetected even in regions where spins are present (Le Doussal and Sen, 1992).

Furthermore, even when considering a specific NAS in an MRI experiment, detecting NMR signals from all nuclear spins of interest within the NAS is impossible. Therefore, the effective diffusion barrier distance may be smaller than the physical distance. The spin packet length Lg is the spatial region in which the NMR-active spins can be detected (Zhang and Hirasaki, 2003). Theoretical studies have indicated that this region, where spins are present but difficult to measure, is influenced by variations in the magnetic field gradient experienced by the sample (Le Doussal and Sen, 1992). If the diffusion distance of the molecules is measured under varying magnetic field gradient strengths, the spin packet length Lg may vary. However, in the experiment, the distance d, a parameter of the magnetic field gradient strength, was held constant between the tip of the needlelike ferromagnetic material and the sample surface, ensuring that the magnetic field gradient remained stable over time. Therefore, as a first approximation, the distance Ls between the diffusion barriers and the observed spin packet length Lg can be considered to be proportional. Consequently, for the interpretation of R2, we choose to use the spin packet length Lg instead of Ls.

The simulation codes as well as datasets generated using the code for this study can be found on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17893540; Kawabata et al., 2025).

NK and NA designed the research and conducted the experiments. TK contributed to theoretical discussions. All authors wrote and reviewed the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This research has been supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant nos. 22k05225 and 25K08761); the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices, grant no.20241302 and 20251279); Gunma University (S-Membrane project); and the Japan Science and Technology Agency under the Support for Pioneering Research Initiated by the Next Generation project (grant no. JPMJSP2146).

This paper was edited by Geoffrey Bodenhausen and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ailion, D. C.: NMR investigations of ultraslow diffusion in incommensurate insulators and in biomedical systems (eg lung), Solid state ionics, 125, 251–256, 1999. a, b

Asakawa, N. and Obata, T.: A utilization of internal/external quasi-static magnetic field gradients: transport phenomenon and magnetic resonance imaging of solid polymers, Polymer journal, 44, 855–862, 2012. a, b

Asakawa, N., Matsubara, K., and Inoue, Y.: Low-dimensional lattice diffusion in solids investigated by nuclear spin echo measurements, Chemical Physics Letters, 406, 215–221, 2005. a

Axelrod, S. and Sen, P. N.: Nuclear magnetic resonance spin echoes for restricted diffusion in an inhomogeneous field: Methods and asymptotic regimes, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 114, 6878–6895, 2001. a

Blumich, B.: NMR imaging of materials, vol. 57, OUP Oxford, ISBN 019850683X, 2000. a

Blümich, B.: Low-field and benchtop NMR, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 306, 27–35, 2019. a

Blümich, B., Perlo, J., and Casanova, F.: Mobile single-sided NMR, Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, 52, 197–269, 2008. a, b

Callaghan, P. T.: Translational dynamics and magnetic resonance: principles of pulsed gradient spin echo NMR, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780191774928, 2011. a

Carr, H. Y. and Purcell, E. M.: Effects of diffusion on free precession in nuclear magnetic resonance experiments, Physical Review, 94, 630–638, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.94.630, 1954. a

Chang, I., Fujara, F., Geil, B., Hinze, G., Sillescu, H., and Tölle, A.: New perspectives of NMR in ultrahigh static magnetic field gradients, Journal of non-crystalline solids, 172, 674–681, 1994. a, b, c

Chang, I., Hinze, G., Diezemann, G., Fujara, F., and Sillescu, H.: Self-diffusion coefficients in plastic crystals by multiple-pulse NMR in large static field gradients, Physical review letters, 76, 2523–2526, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.2523, 1996. a, b, c

Chang, W.-H., Chen, J.-H., and Hwang, L.-P.: Single-sided mobile NMR with a Halbach magnet, Magnetic resonance imaging, 24, 1095–1102, 2006. a

Chao, S.-H., Dougherty, W. M., Garbini, J. L., and Sidles, J. A.: Nanometer-scale magnetic resonance imaging, Review of Scientific Instruments, 75, 1175–1181, 2004. a, b

Chapman, A., Rhodes, P., and Seymour, E.: The effect of eddy currents on nuclear magnetic resonance in metals, Proceedings of the Physical Society. Section B, 70, 345, 1957. a

Dalnoki-Veress, K., Forrest, J., Murray, C., Gigault, C., and Dutcher, J.: Molecular weight dependence of reductions in the glass transition temperature of thin, freely standing polymer films, Physical Review E, 63, 031801-1–031801-10, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.63.031801, 2001. a, b

De Gennes, P.: Glass transitions in thin polymer films, The European Physical Journal E, 2, 201–205, 2000. a

Degen, C., Poggio, M., Mamin, H., Rettner, C., and Rugar, D.: Nanoscale magnetic resonance imaging, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 1313–1317, 2009. a, b

Dias, M., Hadgraft, J., Glover, P., and McDonald, P.: Stray field magnetic resonance imaging: a preliminary study of skin hydration, Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 36, 364–368, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/36/4/306, 2003. a

Doğan, N., Topkaya, R., Subaşi, H., Yerli, Y., and Rameev, B.: Development of Halbach magnet for portable NMR device, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 153, 012047, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/153/1/012047, 2009. a

Doliwa, B. and Heuer, A.: Cage effect, local anisotropies, and dynamic heterogeneities at the glass transition: A computer study of hard spheres, Physical Review Letters, 80, 4915–4918, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.4915, 1998. a

Ediger, M. and Forrest, J.: Dynamics near free surfaces and the glass transition in thin polymer films: a view to the future, Macromolecules, 47, 471–478, 2014. a

Eidmann, G., Savelsberg, R., Blümler, P., and Blümich, B.: The NMR MOUSE, a mobile universal surface explorer, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, Series A, 122, 104–109, 1996. a

Fakhraai, Z. and Forrest, J.: Measuring the surface dynamics of glassy polymers, Science, 319, 600–604, 2008. a

Forrest, J., Dalnoki-Veress, K., Stevens, J., and Dutcher, J.: Effect of free surfaces on the glass transition temperature of thin polymer films, Physical Review Letters, 77, 2002–2005, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.2002, 1996. a, b

Forrest, J. A. and Mattsson, J.: Reductions of the glass transition temperature in thin polymer films: Probing the length scale of cooperative dynamics, Physical Review E, 61, R53, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.61.R53, 2000. a, b

Fryer, D. S., Nealey, P. F., and de Pablo, J. J.: Thermal probe measurements of the glass transition temperature for ultrathin polymer films as a function of thickness, Macromolecules, 33, 6439–6447, 2000. a, b

Fukao, K. and Miyamoto, Y.: Glass transitions and dynamics in thin polymer films: Dielectric relaxation of thin films of polystyrene, Physical Review E, 61, 1743, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.61.1743, 2000. a

Gibbs, S. J. and Johnson Jr., C. S.: A PFG NMR experiment for accurate diffusion and flow studies in the presence of eddy currents, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 93, 395–402, 1991. a

Hahn, E. L.: Spin echoes, Physical review, 80, 580–594, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.80.580, 1950. a

Hürlimann, M. D. and Griffin, D. D.: Spin dynamics of Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill-like sequences in grossly inhomogeneous B0 and B1 fields and application to NMR well logging, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 143, 120–135, 2000. a

Inoue, R. and Kanaya, T.: Heterogeneous dynamics of polymer thin films as studied by neutron scattering, in: Glass Transition, Dynamics and Heterogeneity of Polymer Thin Films, edited by: Kanaya, T., 107–140, https://doi.org/10.1007/12_2012_173, 2012. a

Kawabata, N. and Asakawa, N.: Scanning ex situ solid-state magnetic resonance imaging on polymeric films using a static magnetic field gradient by an electromagnet, Review of Scientific Instruments, 95, 043701-1–043701-8, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0188529, 2024. a

Kawabata, N., Asakawa, N., and Kanki, T.: Power spectral density imaging for polymeric films using ex-situ solid-state magnetic resonance with needlelike ferromagnet, Physical Review E, 110, 054503, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.110.054503, 2024. a, b, c, d, e, f

Kawabata, N., Asakawa, N., and Kanki, T.: Static-gradient NMR imaging for depth-resolved molecular diffusion in amorphous regions in semicrystalline poly(tetrafluoroethylene) film, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281 zenodo.17893540, 2025. a

Keddie, J. L., Jones, R. A., and Cory, R. A.: Size-dependent depression of the glass transition temperature in polymer films, Europhysics Letters, 27, 59–64, https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/27/1/011, 1994. a

Kimmich, R., Unrath, W., Schnur, G., and Rommel, E.: NMR measurement of small self-diffusion coefficients in the fringe field of superconducting magnets, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 91, 136–140, 1991. a, b, c

Korolkov, V.: High Resolution Imaging Of Single Ptfe Molecules On Teflon Surface, NANOScientific Magazine, 21, https://nanoscientific.org/articles/view/134 (last access: 11 December 2025), 2021. a

Landweber, L.: An iteration formula for Fredholm integral equations of the first kind, American journal of mathematics, 73, 615–624, 1951. a

Le Doussal, P. and Sen, P. N.: Decay of nuclear magnetization by diffusion in a parabolic magnetic field: An exactly solvable model, Phys. Rev. B, 46, 3465–3485, 1992. a, b, c

Lin, E. K., Kolb, R., Satija, S. K., and Wu, W.-l.: Reduced polymer mobility near the polymer/solid interface as measured by neutron reflectivity, Macromolecules, 32, 3753–3757, 1999. a, b

Mansfield, P.: Multi-planar image formation using NMR spin echoes, Journal of Physics C, 10, L55, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/10/3/004, 1977. a

Mansfield, P., Maudsley, A., and Bains, T.: Fast scan proton density imaging by NMR, Journal of Physics E, 9, 271, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3735/9/4/011, 1976. a

Mattsson, J., Forrest, J., and Börjesson, L.: Quantifying glass transition behavior in ultrathin free-standing polymer films, Physical Review E, 62, 5187, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.62.5187, 2000. a, b

Meiboom, S. and Gill, D.: Effects of diffusion on free precession in nuclear magnetic resonance experiments, Rev. Sci. Instrum., 29, 688–691, 1958. a

Merabia, S., Sotta, P., and Long, D.: Heterogeneous nature of the dynamics and glass transition in thin polymer films, The European Physical Journal E, 15, 189–210, 2004. a

Nguyen, H. K., Sugimoto, S., Konomi, A., Inutsuka, M., Kawaguchi, D., and Tanaka, K.: Dynamics gradient of polymer chains near a solid interface, ACS Macro Letters, 8, 1006–1011, 2019. a, b

Park, J.-Y. and McKenna, G. B.: Size and confinement effects on the glass transition behavior of polystyrene/o-terphenyl polymer solutions, Physical Review B, 61, 6667, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.61.6667, 2000. a, b

Price, W. S.: Pulsed-field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance as a tool for studying translational diffusion: Part 1. Basic theory, Concepts in Magnetic Resonance: An Educational Journal, 9, 299–336, 1997. a

Price, W. S.: Pulsed-field gradient nuclear magnetic resonance as a tool for studying translational diffusion: Part II. Experimental aspects, Concepts in Magnetic Resonance: An Educational Journal, 10, 197–237, 1998. a

Raich, H. and Blümler, P.: Design and construction of a dipolar Halbach array with a homogeneous field from identical bar magnets: NMR Mandhalas, Concepts in Magnetic Resonance Part B: Magnetic Resonance Engineering: An Educational Journal, 23, 16–25, 2004. a

Roth, C. B. and Dutcher, J. R.: Glass transition and chain mobility in thin polymer films, Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 584, 13–22, 2005. a

Solomon, I.: Relaxation processes in a system of two spins, Physical Review, 99, 559–565, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.99.559, 1955. a

Spencer, R. G. and Bi, C.: A tutorial introduction to inverse problems in magnetic resonance, NMR in Biomedicine, 33, e4315, https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.4315, 2020. a

Takahashi, M., Kikuchi, S., Inoue, N., Sakai, N., Murakami, M., Yokoyama, K., Oka, T., and Nakamura, T.: NMR relaxometry using outer field of single-sided HTS bulk magnet activated by pulsed field, IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity, 32, 1–4, 2022. a

Tanaka, K., Tsuchimura, Y., Akabori, K.-i., Ito, F., and Nagamura, T.: Time-and space-resolved fluorescence study on interfacial mobility of polymers, Applied Physics Letters, 89, 061961-1–061961-2, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2335593, 2006. a, b

Tanaka, K., Tateishi, Y., Okada, Y., Nagamura, T., Doi, M., and Morita, H.: Interfacial mobility of polymers on inorganic solids, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 113, 4571–4577, 2009. a

Tayler, M. C. and Sakellariou, D.: Low-cost, pseudo-Halbach dipole magnets for NMR, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 277, 143–148, 2017. a

Torrey, H. C.: Bloch equations with diffusion terms, Physical Review, 104, 563–565, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.104.563, 1956. a

Westbrook, C. and Talbot, J.: MRI in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-119-39196-8, 2018. a

Yu, I.: A method of analyzing restricted diffusion from spin-echo measurements, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, Series A, 104, 209–211, 1993. a

Zhang, G. Q. and Hirasaki, G. J.: CPMG relaxation by diffusion with constant magnetic field gradient in a restricted geometry: numerical simulation and application, Journal of Magnetic Resonance, 163, 81–91, 2003. a

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results and discussion

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: R2 analyses from CPMG measurements

- Appendix B: Intrinsic R2

- Appendix C: Numerical simulation

- Appendix D: Spin packet length

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results and discussion

- Conclusions

- Appendix A: R2 analyses from CPMG measurements

- Appendix B: Intrinsic R2

- Appendix C: Numerical simulation

- Appendix D: Spin packet length

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References