the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

A novel multinuclear solid-state NMR approach for the characterization of kidney stones

César Leroy

Laure Bonhomme-Coury

Christel Gervais

Frederik Tielens

Florence Babonneau

Michel Daudon

Dominique Bazin

Emmanuel Letavernier

Danielle Laurencin

Dinu Iuga

John V. Hanna

Mark E. Smith

Christian Bonhomme

The spectroscopic study of pathological calcifications (including kidney stones) is extremely rich and helps to improve the understanding of the physical and chemical processes associated with their formation. While Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) imaging and optical/electron microscopies are routine techniques in hospitals, there has been a dearth of solid-state NMR studies introduced into this area of medical research, probably due to the scarcity of this analytical technique in hospital facilities. This work introduces effective multinuclear and multidimensional solid-state NMR methodologies to study the complex chemical and structural properties characterizing kidney stone composition. As a basis for comparison, three hydrates (n=1, 2 and 3) of calcium oxalate are examined along with nine representative kidney stones. The multinuclear magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR approach adopted investigates the 1H, 13C, 31P and 31P nuclei, with the 1H and 13C MAS NMR data able to be readily deconvoluted into the constituent elements associated with the different oxalates and organics present. For the first time, the full interpretation of highly resolved 1H NMR spectra is presented for the three hydrates, based on the structure and local dynamics. The corresponding 31P MAS NMR data indicates the presence of low-level inorganic phosphate species; however, the complexity of these data make the precise identification of the phases difficult to assign. This work provides physicians, urologists and nephrologists with additional avenues of spectroscopic investigation to interrogate this complex medical dilemma that requires real, multitechnique approaches to generate effective outcomes.

- Article

(5403 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Kidney stones (KSs) are a major health problem in industrialized countries. For example, the medical costs associated with the treatment of nephrolithiasis in France exceeds EUR 800 million annually. The study of KSs is presently at the heart of a concerted multidisciplinary axis of research involving physicians, physical chemists and spectroscopists (Bazin et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the nucleation and growth of KSs remains largely unknown, and the associated mechanism is based mainly on assumption and incomplete evidence; hence, more thorough and wide-ranging structural investigations are still required (Sherer et al., 2018; Bazin et al., 2020). The growth of KSs is clearly a multifactorial problem, with their chemical composition and morphology presenting considerable variability due to the extreme complexity of the in vivo reaction media in which they are formed. The resultant biological materials exhibit very different characteristics as they can emanate from wide-ranging pathological scenarios, including bacterial infection, genetic predispositions, diabetes mellitus and bowel diseases (Bazin et al., 2012). Hence, KSs can be considered as being real examples of hybrid organic–inorganic nanocomposite materials.

The main mineral components comprising hydrated calcium oxalates are the monohydrate CaC2O4⋅H2O (whewellite – COM) and dihydrate CaC2O4⋅2H2O (weddellite – COD) species, although amorphous calcium oxalate can also be observed (Gehl et al., 2015; Ruiz-Agudo et al., 2017). The trihydrate form, CaC2O4⋅3H2O (caoxite – COT) is almost never observed in vivo but can be synthesized in an aqueous solution. COD is characterized by a zeolitic structure exhibiting a true structural challenge. It is considered as being one of the very few natural MOFs (metal organic frameworks; Huskić et al., 2016; Dazem et al., 2019), and its chemical formula is better represented by (x≤0.5; Petit et al., 2018). “Structural” and “zeolitic” water molecules are, therefore, distinguished. Calcium phosphates and other mineral phases can also be detected in KSs, i.e., hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), which may be partially carbonated, brushite (CaHPO4⋅2H2O) or struvite (NH4MgPO4⋅6H2O; Gardner et al., 2021). The organic components (from a few percent to a major fraction) include, e.g., proteins (collagen among them), uric acid, lipids, triglycerides, etc. The nature of the organic–inorganic interfaces remain largely unknown to date. This chemical and structural complexity at several scales requires the use of a wide variety of characterization methods. Recently, elaborate experiments took advantage of the last development in TEM (transmission electron microscopy; Gay et al., 2020) and of synchrotron radiation (Bazin et al., 2012). In hospitals, optical microscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), FTIR microscopy, SEM (scanning electron microscopy) and X-ray diffraction are used in routine mode. Curiously, solid-state NMR has been used very rarely in the context of KSs (and other pathological calcifications), apart from sparse 13C and 31P studies (Bak et al., 2000; Jayalakshmi et al., 2009; Reid et al., 2011, 2013; Li et al., 2016; Dessombz et al., 2016), which is unlike other human hard tissues such as bones and teeth. This is probably due to the fact that solid-state NMR instruments are not widely available in hospital settings. It is also stressed that some KSs are small so that the intrinsic lack of sensitivity associated to NMR may be a drawback. Other nuclei, such as 1H and 43Ca, can act as potential NMR targets. However, 1H solid-state NMR remains a rather specialized technique because of the relative inefficiency of magic angle spinning (MAS) in producing really high-resolution data from most systems. 43Ca () is particularly insensitive (as a result of its extremely low natural abundance, ∼0.14 %, and low γ, rad s−1 T−1, 57.2 MHz at 20 T).

In this work, a comprehensive multinuclear solid-state NMR approach is presented that facilitates the detailed structural analysis of KSs and the related synthetic hydrated calcium oxalate phases (COM, COD and COT) associated with their composition. The synthetic phases were obtained by carefully controlling the precipitation of calcium salts in aqueous solutions, as described below in Sect. 6 (Leroy, 2016). In total, nine KSs were studied systematically, with some of them exhibiting similar NMR fingerprints. The spectra of five of them (KS1 → KS5) are presented here. They come from the KS collection of the Tenon hospital (Paris, France) led by Michel Daudon (the collection counts tens of thousands of samples from all origins, exhibiting the largest variety of size, chemical composition and morphology worldwide). Our main goal here is to reach out to the physician community and, more specifically, nephrologists, urologists and biologists. NMR methods are presented at a moderate to high magnetic field (i.e., 7.0 to 16.4 T MHz) in order to make them much more widely accessible. Occasionally, further developments at an ultra-high magnetic field (up to 35.2 T) are proposed to the user. Particular emphasis is placed on high-resolution 1H MAS NMR, with homonuclear decoupling and the complete interpretation of spectra based on structural data, and 43Ca MAS NMR. To the best of our knowledge, these nuclei have never been used as spectroscopic probes for KS studies (apart from a unique 43Ca MAS NMR study by Bowers and Kirkpatrick, 2011). A complete experimental protocol is then presented for the reconstruction of 13C NMR spectra, including organic/inorganic and/or rigid/mobile components. Finally, the intriguing role of phosphates in KSs is partially deciphered by 2D 1H−31P heteronuclear correlation (HETCOR) MAS NMR experiments despite the low phosphate content in KSs.

2.1 CRAMPS (Combined Rotation And Multiple Pulses Spectroscopy) approach

In terms of NMR sensitivity, 1H greatly exceeds that of 13C and 43Ca. Moreover, it is an nucleus, leading to quantitative data much more rapidly if relaxation delays are carefully set. It follows that 1H is a target nucleus in the study of crystalline hydrated calcium oxalate phases and KSs. Moreover, as KSs are bio-nanocomposites, 1H can be considered as being a spectroscopic spy present both in the organic and inorganic components, making the study of the interfaces possible eventually. In the absence of local dynamics, the strong 1H−1H dipolar interaction is a major issue in 1H solid-state NMR, leading to considerable broadening of the resonances. Current trends to reach the highest 1H NMR resolution combine ultra-fast MAS, up to 111 kHz or above (Samoson, 2019), with an ultra-high magnetic field, up to 35.2 T, (Gan et al., 2017), in order to average the strong dipolar couplings. Indeed, the homogeneous character of the homonuclear dipolar interaction implies poor MAS efficiency at low to moderate spinning frequencies (Schmidt-Rohr and Spiess, 1994; note that the temperature increase, inside a 0.7 mm diameter rotor, is estimated to be roughly 20 ∘C in the fast/ultra-fast regime, i.e., νrot>30 kHz). This point is of prime importance as calcium oxalate structures may undergo subtle structural modifications upon heating (Deganello, 1981; Shepelenko et al., 2019; see also Sect. 6). More generally, for a 2.5 mm probe, the temperature increase is <5 ∘C at 5 kHz, and 40 ∘C at 30 kHz. For a 7 mm probe, the order of magnitude is 5 ∘C at 5 kHz.

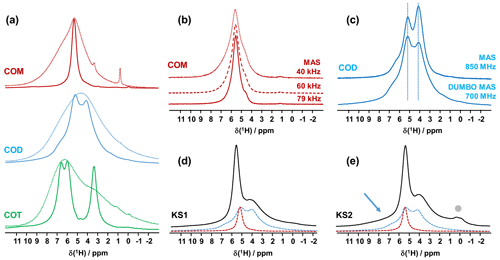

However, such leading edge equipment is not widely available. An alternative is to use the CRAMPS sequence at a moderate spinning frequency (νrot<12 kHz; Paruzzo and Emsley, 2019). The DUMBO sequence (Decoupling Using Mind-Boggling Optimization) belongs to the CRAMPS family (Lesage et al., 2003). Using this approach, the internal temperature increase remains moderate for all rotor diameters. Moreover, this methodology can be successfully implemented on almost all magnets. Moreover, larger rotor diameters may be used, which can be interesting in terms of sensitivity. To the best of our knowledge, synthetic COM, COD and COT samples were never investigated by 1H high-resolution solid-state NMR. The corresponding spectra are presented in Fig. 1. At νrot = 12 kHz, standard 1H MAS NMR spectra (Fig. 1a) are all characterized by very broad and almost featureless line shapes. Such spectral fingerprints are not useful for analytical purposes due to the strong overlap of the resonances. DUMBO decoupling leads to a drastic increase in resolution and to very characteristic features for each synthetic hydrate.

Figure 1(a) 1H MAS (dashed lines) and 1H DUMBO MAS (solid lines) NMR spectra of COM (in red), COD (in blue) and COT (in green; νrot=12 kHz, 700 MHz, 16.4 T). Only the isotropic resonances are represented. (b) 1H very fast MAS (40, 60 and 79 kHz) NMR spectra of COM at a very high magnetic field (850 MHz). (c) Comparison of the 1H NMR spectra of COD obtained under DUMBO MAS (νrot=12 kHz, 700 MHz) and very fast MAS (νrot=79 kHz, 850 MHz) conditions. Vertical dashed lines are for illustration purposes only. (d) 1H DUMBO MAS NMR spectrum of KS1 (νrot=12 kHz, 700 MHz). The red and blue dashed lines correspond to the experimental 1H DUMBO MAS NMR spectra of COM and COD, respectively. (e) 1H DUMBO MAS NMR spectrum of KS2 (νrot=12 kHz, 700 MHz). The plain light gray circle indicates the presence of organic components in KS2. The blue arrow indicates the superposition of organic components (aromatic region) and the deshielded shoulder of COD.

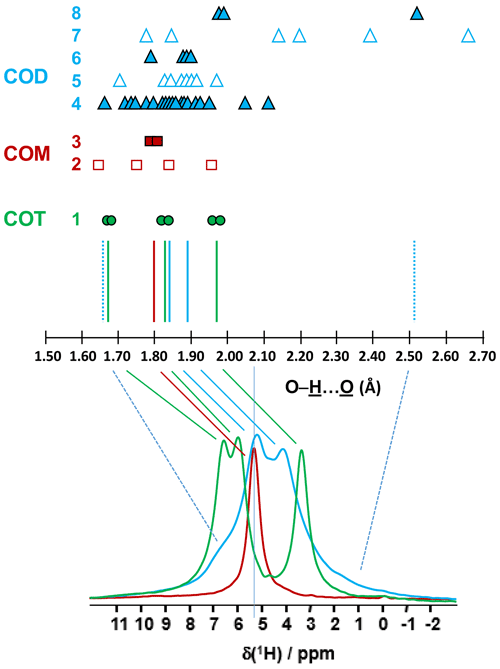

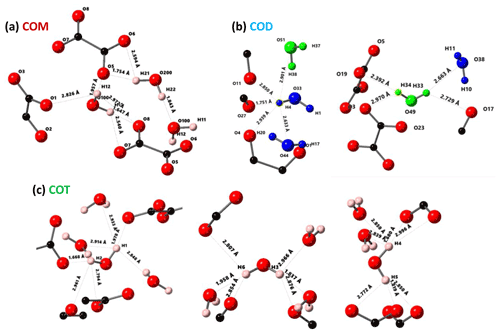

The COT crystallographic structure exhibits six inequivalent sites for protons (Heijnen et al., 1985), whereas only three resonances are clearly observed at δiso(1H)=3.36, 5.95 and 6.53 ppm (parts per million; Fig. 1a). A realistic assumption is that some resonances are so close that they cannot be distinguished even under DUMBO decoupling. It has been shown previously (Eckert et al., 1988; Pourpoint et al., 2007) that δiso(1H) can be related to the shortest bond length in hydrogen bond networks. The general trend is that δiso(1H) strongly increases with the shortening of . Interestingly, the six nonequivalent hydrogens can be distinguished based on distances, leading to three distinct groups (Fig. 2 and Table A1 in the Appendix), namely 1.668–1.679 Å/1.809–1.837 Å/1.957–1.978 Å. It is stressed here that the distances were obtained after extensive optimization of the geometry of the COT structure at density functional theory (DFT) level (the same comment holds for the COM and COD structures; see Sect. 6). According to the literature (Pourpoint et al., 2007), a variation in of ∼0.3 Å is related to a δiso(1H) variation of ∼3.5 ppm, which is in rather good agreement with the results presented here (i.e., the shorter the distance, the higher the isotropic 1H chemical shift). We mention also (Table A1) that each proton of the structure is involved in a relatively high number of contacts (from three to four, with Å). The 3Å cut-off is realistic when considering “weak” H bonds (Steiner, 2002). In other words, the shortest distance directly dictates δiso(1H), whereas the number of contacts is more representative of the electrostatic/dispersion contributions at a given H position (Steiner, 2002). As all protons of COT are characterized by a large number of contacts, we assume a certain character of “rigidity” in the structure at room temperature and very limited local dynamics (Fig. 3c). Under this simple assumption, at most three resolved δiso(1H) are expected due to similarities in distances (see above), which is in good agreement with the experimental data (Fig. 1a). Therefore, the 1H COT assignments are the following, using the numbering given in Table A1: 3.36 ppm for H1/H6, 5.95 ppm for H3/H5 and 6.53 ppm for H2/H4. We note that partial deuteration could be of great help in increasing the resolution further.

Figure 2Prediction of the relative positions of δiso(1H) for COM (red), COD (blue) and COT (green) as a function of the shortest distances (in Ångström; hereafter Å). The general rules are as follows: (i) for a given distance, a δiso(1H) is associated (vertical colored solid lines), and (ii) if local dynamics are present, averaged distances are first calculated. All distances are derived from optimized geometries at the DFT level (Table A1 and Sect. 6). The effect of eventual local dynamics in the case of the “less rigid” structure is taken into account. For line 1, the structure of COT is considered as being “rigid” (plain green circles). On the basis of the shortest distance, the six inequivalent protons can be associated in three groups. To each group, a single average δiso(1H) is assigned. A total of three lines for COT is predicted (represented by the three vertical green solid lines). For line 2, the structure of COM is considered as being less rigid (open squares), while for line 3 the corresponding averaged distances are represented by plain squares. A single average δiso(1H) is associated as the averaged distances are very close. A total of one line for COM is predicted. The COD case is shown in lines 4 to 8, where COD exhibits both rigid (plain triangles; line 4) and less rigid water molecules (open triangles in line 5 for the four structural water molecules and in line 7 for the three zeolitic water molecules). For line 6, the corresponding averaged distances for the structural water molecules are represented by plain triangles, and for line 8, the corresponding averaged distances for the zeolitic water molecules are represented by plain triangles. A continuum of δiso(1H) is predicted for COD. The vertical blue dashed lines correspond to the expected limits of δiso(1H). The two vertical solid blue lines correspond to local maxima, adding lines 4, 6 and 8. At the bottom, the superposition of the 1H DUMBO MAS NMR spectra for COM (red), COD (blue) and COT (green; see Fig. 1a) is shown. The solid and dashed lines connect the experimental data and the predicted δiso(1H).

In the case of COM, the four H crystallographic sites (H11, H12, H21 and H22; Deganello, 1981) are characterized by a large range of distances (from 1.647 to 1.957 Å) and a restricted number of contacts (from 1 to 3; Table A1). Therefore, a less rigid structure is expected at room temperature (when compared to COT). Rapid flips of H2O molecules could lead to partial averaging of δiso(1H) of protons belonging to the same molecule (Fig. 3). Using the numbering given in Table A1, the average distances for H11/H12 and H21/H22 are very similar (i.e., 1.802 and 1.795 Å, respectively). A unique resonance is therefore expected, which is in full agreement with the 1H DUMBO MAS NMR spectrum of COM (one resonance centered at 5.26 ppm; Figs. 1a and 2). Data obtained at 100 K (see Fig. A2) demonstrated the presence of four resolved 1H resonances for COM. It is worth noting that δiso(1H) for H11, H12, H21 and H22 in COM and H3/H5 in COT are experimentally in very close agreement with the associated distances. From one synthetic sample to the other, δiso(1H) may vary slightly under DUMBO conditions (∼0.3 ppm). COM is always obtained as a final product, as shown by the X-ray powder diffraction (XRD). Subtle variations are observed, depending on the degree of the disorder present, as demonstrated very recently by Shepelenko et al. (2019).

Figure 3Structural details of COM (a), COD (b) and COT (c). For each proton of the water molecules, the shortest distance (in Å) is represented, together with the number of contacts (3 Å cut-off). For COT, the number of contacts is high (three to four), and the COT structure is considered as being rigid. In the case of COD, the structural and zeolitic water molecules are represented in blue and green, respectively. A selection of rigid (H4) and less rigid (H33 or H34) water molecules is presented. All distances and the number of contacts are summarized in Table A1. Color code: red is O, black is C and light pink is H.

The 1H spectrum of COD (Fig. 1a) is a priori complex, as it corresponds to the superposition of structural and zeolitic water molecules (Tazzoli and Domeneghetti, 1980; Izatulina et al., 2014). It is much broader than the spectra corresponding to COM and COT. More specific features centered at δiso(1H)=4.11, 5.17 and ∼6.5 (shoulder) ppm are observed (Fig. 1a). When compared to the COT spectrum, the spectral resolution decreases, as expected, from the partial disorder of the zeolitic water molecules. The detailed examination of selected distances (Table A1) allowed us to propose a partial assignment of the resonances. For that purpose, a model (relaxed at the DFT level), which corresponds to , was first calculated (or Ca8C16O32(H2O)16(H2O)3). The water molecules located in the channels of the zeolitic structure are represented in italics in the preceding formula. Taking into account the number of contacts (in full analogy with the approach described above for COM and COT), among the 19 water molecules, seven molecules are considered as being less rigid (or potentially mobile), of which four of them are structural and three are zeolitic. The remaining 12 water molecules are considered as being rigid. Typical example of rigid (H4) and less rigid (H33/H34) water molecules are presented in Fig. 3b. From Fig. 2, it is then possible to predict the expected ranges of δiso(1H) for COD. The rules applied are that rigid water molecules correspond to two distinct δiso(1H) (line 4), whereas less rigid water molecules correspond to a single average δiso(1H) (averaging of line 5 gives line 6; averaging of line 7 gives line 8). The sum of lines 4, 6 and 8 (in blue) corresponds to the expected 1H spectrum for COD. On this basis, it is expected (i) that δiso(1H) is distributed over a much larger range when compared to COM and COT and (ii) that some maxima should be observed (at least two, corresponding to large number of overlapping triangles in Fig. 2). Points (i) and (ii) are in very good agreement with the experimental observations. All in all, the relative predicted positions for δiso(1H) resonances are in agreement with the experimental data for COM, COD and COT (bottom of Fig. 2), validating the proposed assignments.

As a first conclusion of this section, 1H DUMBO MAS NMR spectra for COM, COD and COT correspond to useful fingerprints for analytical purposes as they are clearly characteristic for each phase. Such fingerprints can be used for the analysis of 1H NMR spectra of KSs (see below). We emphasize that 1H spectra with an excellent signal-to-noise ratio were obtained within minutes. As δiso(1H) values are very sensitive to H-bond networks and to local motional averaging, studies performed on synthetic COM, COD and COT were necessary prior to the detailed analyses of KSs. Nevertheless, the following comments have to be made at this stage: (i) first, the 1H DUMBO MAS methodology (νrot=12 kHz, 700 MHz) is comparable to the very fast MAS/very high magnetic field approach (νrot∼80 kHz, 850 MHz) without any multiple pulses decoupling. In Fig. 1b, the 1H MAS NMR spectra of COM are presented at various fast/very fast rotation frequencies, from νrot=40 to ∼80 kHz. As in the case of the DUMBO MAS approach, a single resonance (with a small shoulder) was observed, showing a continuously decreasing linewidth with increasing the MAS frequency. The linewidth obtained at ∼80 kHz is still broader than the one observed under DUMBO MAS conditions. In Fig. 1c, the two approaches are compared in the case of COD. The resolution is slightly enhanced under very fast MAS at 79 kHz, but it remains comparable to DUMBO conditions at 12 kHz. More importantly, the relative intensities are not strictly preserved, indicating that some distortions of the line shapes may occur under DUMBO conditions. It follows that only semi-quantitative data can be extracted, at best, in the case of complex mixtures of hydrated calcium oxalate phases. Moreover, dynamics at room temperature may impact the efficiency of the DUMBO decoupling.

Finally, two KSs (KS1 and KS2) were studied by 1H DUMBO MAS NMR (Fig. 1d and e). In the case of KS1, a mixture of COM and COD is immediately detected (in full agreement with FTIR and XRD; not shown here). As stated above, a slight deviation of δiso(1H) for COM is observed. A semi-quantitative analysis of the COM/COD proportions is possible and could be systematically compared to FTIR analyses (as routinely obtained in hospitals). In addition to COM and COD resonances, the 1H DUMBO MAS NMR spectrum of KS2 exhibits small new contributions that can be attributed to organic moieties (such as proteins). In this case, a semi-quantitative analysis of the KSs appears more difficult to perform. Working at much higher magnetic field, 35.2 T (Gan et al., 2017), and under ultra-fast MAS (≫100 kHz) should lead to increased resolution and easier direct quantification of the spectra. Finally, we mention the fact that DUMBO experiments may be sensitive to local dynamics, especially in the intermediate regime (Paruzzo and Emsley, 2019). It may involve some discrepancies between 1H and 13C NMR data in terms of quantification (see Sect. 4).

2.2 editing and 1H−1H double-quantum (DQ) experiments

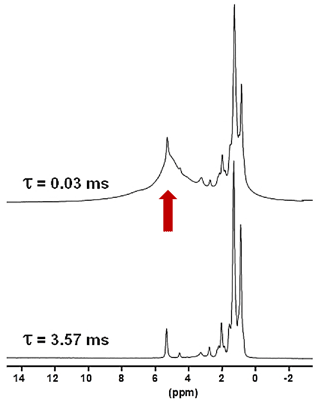

Another KSs sample, KS3, that was studied contained a large proportion of organic moieties (as shown by FTIR). Another option to increase the 1H NMR resolution is to implement standard Hahn echoes with increasing delays, τ, (up to several milliseconds) and synchronization with the MAS frequency. The magnetization associated to the protons characterized by short will dephase very rapidly. 1H MAS echoes (νrot=30 kHz) for KS3 are presented in Fig. 4. From XRD data (not shown here) confirmed by 13C CP MAS NMR data (see Sect. 4), KS3 contains COM as a major mineral phase. For long τ, sharp lines (associated to mobile components) were obtained, whereas the broader COM component, around 5.2 ppm, was totally suppressed. δiso(1H) values agree with unsaturated fatty acids (δiso(1H)∼5.25 ppm; Ren et al., 2008). The presence of triglycerides is excluded as the and resonances of the glycerol backbone (δiso(1H)∼5.0 and 4.0 ppm, respectively) were not detected.

Figure 41H Hahn echo MAS NMR spectra for KS3 recorded at 16.4 T. τ was synchronized with the rotation frequency, which is shown here as νrot=30 kHz. No temperature control was implemented, leading to a ∼40 ∘C increase in the sample temperature and the associated increase in local dynamics. The vertical red arrow corresponds to the resonance coming from COM (see also Fig. 1a and b).

Such a level of resolution allowed for the implementation of J-MAS-derived pulse schemes, such as the 1H−1H double quantum-filtered (DQF) correlation spectroscopy (COSY) MAS experiment (based on isotropic J(1H−1H) couplings). This experiment is part of the toolbox for a more general dynamics-based spectral editing research topic applied to biological solids (Mroue et al., 2016; Matlahov and van der Wel, 2018; Gopinath and Veglia, 2018). The 1H−1H DQF COSY MAS spectrum is presented in Fig. 5a for KS3. All resonances of the mobile fatty acid chains were assigned in a straightforward way, demonstrating the pertinence of this through-bond correlation experiment. On the other hand, dipolar-based double quantum (DQ) experiments can be implemented to establish through-space proximities between protons (such as back to back or BABA; Feike et al., 1996). It is a distinct advantage to perform such experiments under very fast MAS (here 79 kHz). Indeed, the spectral resolution is drastically increased, leading to an easier observation of the correlation peaks. The 1H−1H DQ BABA MAS NMR spectrum of KS3 is presented in Fig. 5b. The 1H resonance corresponding to the COM phase is clearly evidenced on the 1H projection and on the 2D diagonal (red arrows). Moreover, red dashed ovals indicate correlations involving the protons of the immobile proteins contained in KS3 (essentially the , 1Hα−1Hβ regions). 1H spin diffusion experiments should help to highlight actual correlations between the organic and inorganic components at the interface (Schmidt-Rohr and Spiess, 1994).

Figure 5(a) 1H−1H DQF COSY MAS NMR spectrum for KS3 at νrot=30 kHz recorded at 16.4 T. Here, no temperature control was implemented, leading to a ∼40 ∘C increase in the local temperature and, therefore, of local dynamics. All peaks are assigned to contributions from unsaturated mobile fatty acids (with unsaturations). (b) 1H−1H DQ BABA MAS NMR spectrum for KS3 at νrot=79 kHz recorded at 16.4 T (no temperature control; SQ–SQ, single quantum–single quantum, representation). The recoupling period is two rotor periods. Off-diagonal correlations (immobile organic moieties) are highlighted by dashed red ovals. The red arrows indicate the COM contribution.

Natural abundance solid-state 43Ca MAS NMR spectroscopy remains a challenge. Indeed, the NMR characteristics of this quadrupolar nucleus () are clearly unfavorable, as natural abundance is 0.14 % and low γ (ν0=57.2 MHz at 20 T). Nevertheless, the following four main experimental approaches have been successfully developed during the last few years: (i) using large volume rotors (7 mm; ∼400 mg of sample) at high magnetic field (20 T), under moderate MAS (∼5 kHz) and implementing DFS (double frequency sweep) excitation scheme (Sect. 6); (ii) using much smaller rotors (3.2 mm; ∼20 mg of sample at ultra-high magnetic field (35.2 T) and under moderate/fast MAS (∼18 kHz); (iii) using dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) to strongly enhance the 43Ca polarization, usually in the indirect mode (from 1H to 43Ca); (iv) using labeling in 43Ca (starting from an enriched calcite precursor; Laurencin et al., 2021; Smith, 2020; Laurencin and Smith, 2013). Here, we follow the approach in (i), which is by far the easiest to implement in most NMR facilities worldwide (as long as a low γ probe is available).

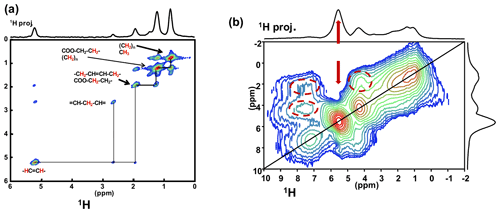

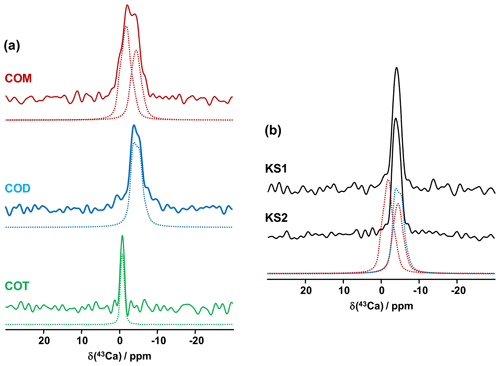

The first contributions related to the study of synthetic calcium oxalates hydrates by 43Ca MAS NMR spectroscopy were proposed by Wong et al. (2006) for COT and by Bowers and Kirkpatrick (2011) for the three hydrated phases. The latter claimed that the COM line shape could be attributed to an averaged Gaussian signal due to a local disorder in the structure (Tazzoli and Domeneghetti, 1980). Colas et al. (2013) demonstrated that a high signal-to-noise ratio is necessary to extract reliable quadrupolar parameters from natural abundance 43Ca MAS NMR spectra and reinvestigated the COM phase. Instead of a Gaussian contribution, two distinct resonances were evidenced, which is in agreement with the crystallographic data ( ppm, CQ=1.50 MHz, ηQ=0.60; δiso(43Ca)=0.7 ppm, CQ=1.60 MHz, ηQ=0.70). The 43Ca MAS NMR spectra of COM, COD and COT, recorded at 20.0 T, are presented in Fig. 6a. All spectra were obtained in natural abundance in a reasonable amount of experimental time (∼2 h for COM and COT; ∼4 h for COD). The 43Ca NMR fingerprints obtained allow for unambiguous distinctions of the three phases. The sharpest line (characterized by the smallest CQ) is observed for COT (one unique crystallographic site). For this particular phase, second-order quadrupolar broadening is efficiently suppressed at 20 T, leading directly to ppm. This value is slightly different from the one reported by Wong et al. (2006; i.e., −4.2 ppm). Such a discrepancy can be attributed to a difference in chemical shift referencing (Gervais et al., 2008). The associated quadrupolar parameters for COT (Wong et al., 2006) were CQ=1.55 MHz, ηQ=0.72. CQ is probably overestimated, as such a value would definitely produce second-order quadrupolar broadening under MAS at 20.0 T (see above the quadrupolar parameters for COM). Finally, a rather featureless spectrum is obtained for COD (one crystallographic site), exhibiting a much larger linewidth than for COT ( ppm, CQ∼1.60 MHz, ηQ∼0.20). We assign this broadening to the distribution of zeolitic water molecules (leading consequently to a slight distribution of δiso(43Ca)). Hence, it is demonstrated that natural abundance 43Ca MAS NMR spectroscopy is useful for characterizing hydrated calcium oxalate phases. The use of moderate MAS is sufficient to retrieve a satisfactory resolution as characteristic CQ(43Ca) are usually small/very small (<1.8 MHz). However, the δiso(43Ca) range covered by these three phases is making this NMR parameter less sensitive to distinguishing the hydrates. This comes from the fact that δiso(43Ca) is mainly determined by the coordination of the Ca atoms and the mean distances. These parameters are almost identical for COM, COD and COT (eight-fold coordination for COM and COD; seven-fold coordination for COT; range of averaged Ca−O distances, i.e., 2.47–2.49 Å). This last comment is rather in contradiction with previous conclusions proposed in the literature (Bowers and Kirkpatrick, 2011).

Figure 6(a) Natural abundance 43Ca MAS NMR spectra of COM (red), COD (blue) and COT (green) recorded at 20.0 T (νrot=3 to 5 kHz). The dashed lines correspond to fits. (b) Natural abundance 43Ca MAS NMR spectra of KS1 and KS2. The red dashed lines correspond to the two resonances associated to COM. The blue dashed line corresponds to the 43Ca MAS NMR spectrum of COD.

The natural abundance 43Ca MAS NMR spectra of KS1 and KS2 are presented in Fig. 6b. They are largely similar to the COD spectrum overall. The contribution of a COM component is hardly discernable (though it is present, especially in KS1; see Fig. 7). As stated above, the structure of COM is subject to subtle structural variations which could lead to the overlap of the two 43Ca resonances. In other words, though interesting in principle, natural abundance 43Ca MAS NMR spectroscopy (inherently associated with the limited signal-to-noise ratio) should not be used as a first solid-state NMR tool of investigation for KSs. However,43Ca NMR would benefit from working at a ultra-high magnetic field (35 T) in order to drastically increase the resolution and enhance 43Ca NMR analytic capabilities.

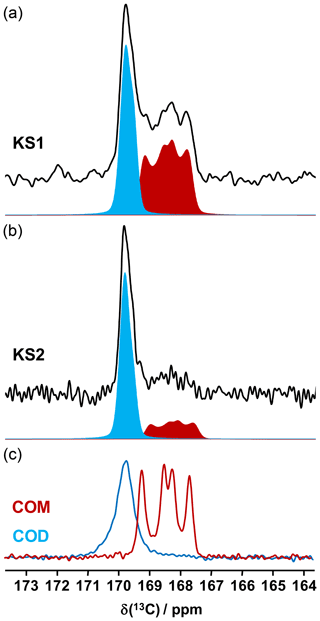

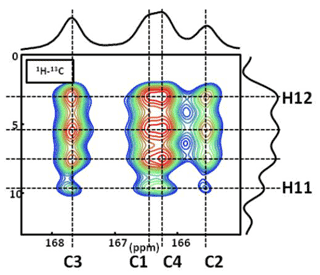

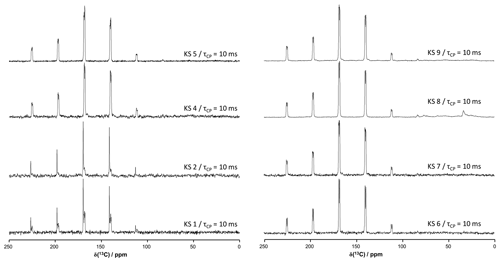

13C NMR data related to synthetic calcium oxalate phases and KSs are the most represented in the literature. This is probably due to the fact that the spectral resolution is high under MAS and that CP (cross-polarization) MAS experiments can easily be implemented even at low or moderate magnetic field. Typical 13C CP MAS NMR spectra for COM and COD are presented in Fig. 7. A total of four isotropic resonances are observed for COM, as expected from XRD data (Colas et al., 2013), and one unique broader resonance is observed for COD, as expected from XRD data, considering the disorder associated to the zeolitic water molecules. Such a disorder has an impact on the resolution of the 13C NMR spectra.

It is observed that the chemical shift range of interest is very restricted (∼4 ppm from 167 to 171 ppm), corresponding to ∼0.8 % of the whole 13C isotropic chemical shift range. 13C CP MAS NMR spectra for KS1 and KS2 are also presented in Fig. 7. The presence of COM and COD components is clearly evidenced and could be quantified if necessary (by increasing the signal-to-noise ratio, , significantly). The is adequate here for coarse quantification. For better accuracy, a longer experimental time will be necessary. Moreover, NMR experiments will be combined with denoising techniques developed recently by Laurent and Bonhomme (2020).

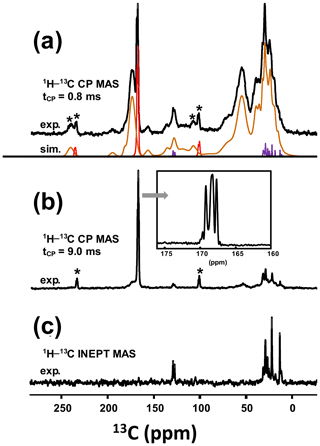

As a matter of fact, a single experiment at fixed contact time (usually >5 ms) is sufficient, in principle, for quantitative purposes, as 1H−13C dipolar couplings are comparable for all 13C sites (differences in relative intensities can be evidenced at much short contact time, i.e., <0.5 ms). The case of KS3 is by far more complex. As stated in Sect. 1, a given KS may include a complex organic component containing lipids, triglycerides, membrane components, glycoproteins (like the Tamm–Horsfall protein) and glycosaminoglycans, among other species (Reid et al., 2011). The approximate chemical composition of KS3 is ∼10 % proteins, ∼20 %–25 % COM and ∼65 % amorphous silica (Dessombz et al., 2016). In Fig. 8, we propose a robust protocol to reconstruct the 13C MAS NMR spectra starting from well-identified subspectra. At a short contact time (0.8 ms), all carbon-containing species are detected, corresponding to both sharp and broad lines (Fig. 8a).

Figure 8(a) 13C CP MAS NMR spectrum of KS3 (recorded at 7.0 T using a short contact time, i.e., 0.8 ms; νrot=5 kHz). The experimental spectrum is decomposed into the following three components: COM (in red), fatty acids (in purple) and proteins (in brown). (b) 13C CP MAS NMR spectrum of KS3 (recorded at 7.0 T using a long contact time, i.e., 9.0 ms). The inset highlights the COM contribution (four resonances, with two of them almost overlapping; Colas et al., 2013). (c) 1H−13C refocused INEPT J-MAS NMR spectrum of KS3 (recorded at 7.0 T). The unsaturations of the fatty acids are clearly evidenced at δiso(13C)∼130 ppm. The asterisk (*) indicates the spinning sidebands.

Then, a T1ρ(1H) filter was applied by increasing the contact time by a factor of ∼10, leading to the drastic reduction in the intensities of the broad components. The four resonances of COM are clearly observed (insert in Fig. 8b). COD is absent, which is in agreement with powder XRD and FTIR data. It follows that the proton spin baths corresponding to COM and the broad components are independent; spin diffusion and domain size measurements could be implemented as complementary experiments (Schmidt-Rohr and Spiess, 1994). The 1D 1H−13C refocused INEPT J-MAS NMR sequence (Fig. 8c) allowed a selective extraction of the mobile components corresponding to the fatty acids (see also Fig. 5a). The unsaturated nature is clearly evidenced by the shift at δiso(13C)∼130 ppm. Finally, the 13C CP MAS NMR spectrum (Fig. 8a; bottom) could be reconstructed with resonances from (i) the COM phase and its associated spinning sidebands (in red), (ii) fatty acids characterized by very sharp lines (in purple) (iii) and proteins (in brown; Cavanagh et al., 2007), for which a precise attribution cannot be given at this stage.

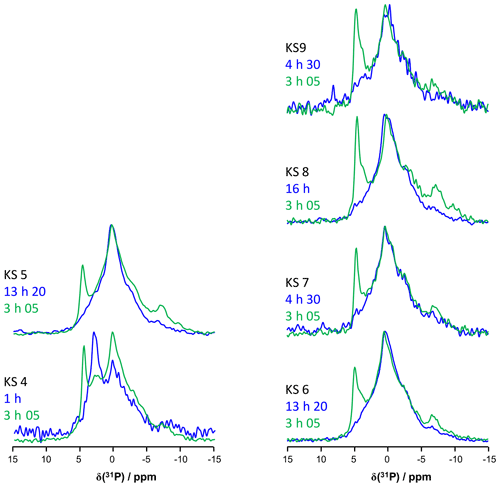

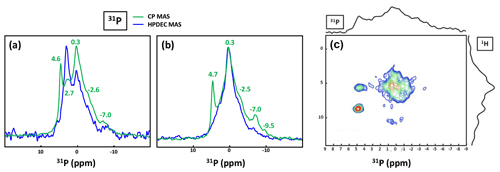

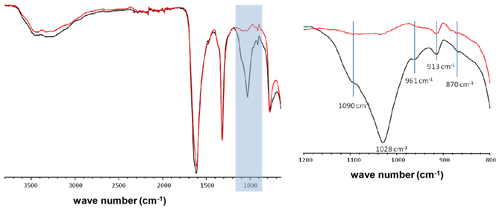

Bak et al. (2000) used 31P MAS and CP MAS experiments to evidence phosphate-containing phases in KSs. The presence of phosphate groups in KSs is not unusual and is observed mainly by FTIR (Fig. A1). However, their exact chemical nature remains unclear. Phosphates in KSs can correspond to (i) mineral phases, such as substituted (carbonated) hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), brushite (CaHPO4⋅2H2O) or struvite (NH4MgPO4⋅6H2O), and (ii) organic phosphates present in phospholipids (in the cell membrane) and/or DNA, RNA and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules (Butusov and Jernelöv, 2013). Usually, phosphates are found as minor components in KSs, making 31P NMR attractive given the high inherent signal sensitivity of 31P (which is also an nucleus). A total of six KSs (exhibiting COM as the major phase and the apparent absence of phosphate phases by powder XRD) were studied here. The representative 31P MAS and CP MAS NMR spectra of the KSs are presented in Fig. 9.

Figure 9(a) 31P MAS under high-power {1H} decoupling (in blue) and CP MAS (in green) under high-power {1H} decoupling NMR spectra of KS4. Some specific chemical shifts are highlighted. (b) 31P MAS under high-power {1H} decoupling (in blue) and CP MAS (in green) NMR spectra of KS5 (representative of an ensemble of five KSs). Some specific chemical shifts are highlighted. (c) 1H−31P HETCOR CP MAS NMR spectrum of KS4 (temperature control at −20 ∘C). All spectra shown here were recorded at 16.4 T.

The 31P NMR fingerprint of KS4 is specific (Fig. 9a), whereas KS5 has a 31P fingerprint analogous to four other KSs (Fig. 9b). The acquisition time is ∼2 to 3 h, demonstrating that the amount of phosphate species is indeed small in all samples. One notes a large distribution of δiso(31P), corresponding not only to structural disorder but also to strong chemical variability. In order to facilitate the assignment of δiso(31P), 1H−31P HETCOR CP MAS NMR experiments under active temperature control ( ∘C) were implemented as well (Fig. 9c). In total, three clear correlations were observed, i.e., , and δiso(31P)∼0.25–. Reasonable assignments are the following (Godinot et al., 2016): (i) the peak centered at δiso(31P)=4.6 ppm is assigned to struvite, i.e., NH4MgPO4⋅6H2O (Bak et al., 2000). The correlation centered at (ammonium groups) is attributed to . The correlation centered at concerns water molecules. It is interesting to note that the amount of struvite is extremely small (almost absent in the 31P MAS NMR spectrum of KS4 and KS5; Fig. 9a and b). (ii) The resonance at δiso(31P)=0.3 ppm may be attributed to phosphates in phospholipids (in this case, δiso(31P) is in the ∼1 to −1 ppm range). However, correlations with δiso(1H)<3 ppm are almost absent (such resonances should be characteristic for long alkyl chains in phospholipids). Consequently, we assign the 31P resonance to inorganic (hydrated) orthophosphates. (iii) δiso(31P)∼2.7 ppm could be potentially assigned to amorphous calcium phosphate with a rather small (rather unusual) level of protonation (this resonance is underestimated in the CP MAS experiment; Fig. 9a). (iv) δiso(31P)≪0 ppm resonances are assigned to pyro- and/or polyphosphates. The 13C CP MAS NMR spectra and 31P (MAS and CP MAS) NMR spectra of all samples studied here are given in Figs. A3 and A4, respectively.

Synthesis. Calcium chloride (CaCl2) and sodium oxalate (Na2C2O4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. All syntheses were carried out using distilled water. For COM, at 40 ∘C, equimolar aqueous solutions of Na2C2O4 and CaCl2 (0.1 mol. L−1) were added simultaneously, dropwise, in a few milliliters of water under magnetic stirring. The mixture was left mixing under these conditions during 2 h before filtration and was then washed with cold water before drying under air. For COD, a Na2C2O4 aqueous solution (0.1 mol. L−1) and a CaCl2 solution (1.0 mol. L−1, Ca/Ox =10) were prepared the day prior to the reaction and stored between 2–6 ∘C overnight. The solution of Na2C2O4 was added dropwise to the CaCl2 solution in an ice bath (T<7 ∘C) under magnetic stirring. The mixture was left under stirring for 15 min before filtration and was then washed with cold water before drying under air. For COT, in an ice bath, two equimolar (0.001 mol. L−1) aqueous solutions of Na2C2O4 and CaCl2 were slowly added simultaneously, dropwise, in a few milliliters of water under vigorous magnetic stirring. The mixture was left under stirring for 15 min before filtration and was then washed with cold water before drying under air. All COM, COD and COT samples were obtained as white fine powders. COD and COT were rapidly stored between 2–6 ∘C, while COM could be stored at ambient temperature.

Kidney stones. The samples were provided by Michel Daudon (Tenon Hospital, Paris, France). The choice of the diameter of the used NMR rotor was dictated by the initial size of the KSs and the implemented experiments. In the case of large KSs, smaller pieces were studied as powders by NMR.

NMR methods. Warning: the COM structure is highly sensitive to temperature variations (≥15 ∘C). The lowest MAS frequencies have to be implemented for all investigated nuclei and active regulation of the sample temperature (Bruker BCU-Xtreme cooling unit). Most of the 1H MAS and DUMBO MAS NMR spectra presented in Fig. 1 were obtained at 700 MHz (Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer), using a 2.5 mm Bruker MAS probe spinning the sample at 12 kHz (20 to 40 scans; 10 s recycle delay for quantitative measurements; 10 ∘C in temperature; µs; 24 µs duration of the shape length at 113 kHz radio frequency (RF) field). The DUMBO experiment was first set up with glycine as a test sample (including the scaling of the isotropic chemical shift) and then optimized for each compound. Some 1H MAS NMR spectra were obtained at 850 MHz, using a 1 mm JEOL MAS probe (spinning the sample up to 79 kHz; four scans; 3 s recycle delay; µs). Synchronized Hahn echoes (Fig. 4) were performed at 700 MHz, using a 2.5 mm Bruker MAS probe spinning the sample at 30 kHz (64 scans; 5 s recycle delay; µs; no active regulation of the temperature in order to increase local dynamics; the increase in temperature is estimated to ∼40 ∘C). The 1H−1H DQF COSY MAS NMR experiment (Fig. 5) was performed at 700 MHz, using a 2.5 mm Bruker MAS probe at 30 kHz (32 scans; 2 s recycle delay; µs; 256 increments in t1 dimension; no active regulation of the temperature in order to increase local dynamics and magnitude mode). The 1H−1H SQ-DQ BABA MAS NMR experiment (Fig. 5) was performed at 850 MHz, using a 1 mm JEOL MAS NMR probe spinning the sample at 79 kHz (16 scans; 3 s recycle delay; µs; two BABA loops, 426 increments in t1 dimension and no active regulation of the temperature). All 1H NMR spectra were referenced using adamantane (1.85 ppm) as a secondary reference. All natural abundance 43Ca NMR spectra (Fig. 6) were obtained at 850 MHz (Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer), using a 7 mm low-γ Bruker MAS single channel NMR probe spinning the sample at 3 to 5 kHz. A DFS (double frequency sweep; Iuga et al., 2000) enhancement scheme, followed by a 90∘ selective pulse of 1.5 µs, was used (DFS pulse length of 2 ms, RF ∼8 kHz and a convergence sweep from 400 to 50 kHz; 5600 to 18 000 scans; 0.8 s recycle delay). All 43Ca chemical shifts were referenced at 0.0 ppm to a 1.0 mol. L−1 aqueous solution of CaCl2 (Gervais et al., 2008). The 1H−13C RAMP (ramped amplitude) CP MAS experiments (Fig. 7) were obtained at 700 MHz (Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer) using a 2.5 mm Bruker MAS double resonance NMR probe spinning the sample at 5 kHz (600 to 1200 scans; 3 s recycle delay; µs; 2 to 8 ms contact time). The 13C MAS NMR spectra presented in Fig. 8 were obtained at 300 MHz (Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer) using a 7 mm Bruker MAS double resonance NMR probe spinning the sample at 5 kHz (328 scans; 3 s recycle delay; µs; 0.8 and 9.0 ms contact time; refocused INEPT MAS: 6000 scans; 3 s recycle delay; 5.2 and 3.2 µs pulse on 1H and 13C respectively; no active regulation of the temperature). All 13C NMR spectra were referenced using adamantane (38.48 ppm) as a secondary reference. 31P 1D and 2D NMR spectra presented in Fig. 9 were obtained at 700 MHz (Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer) using a 2.5 mm Bruker MAS double resonance NMR probe spinning the sample at 30 kHz (≈4000 scans for high-power {1H} decoupling experiments and ≈3700 for CP MAS experiments; recycle delay: 10 s for high-power {1H} decoupling experiments; 30∘ flip angle; 3 s for CP MAS experiments; µs; 5.0 ms contact time for CP MAS experiments). For the 1H−31P HETCOR RAMP CP MAS experiment, the number of scans was 400, the recycle delay was 3 s, µs, the contact time was 5.0 ms, with 96 increments in t1 dimension, and there was an active regulation of the temperature at −20 ∘C.

Relaxation of crystallographic structures. Starting from the crystallographic data, COM (Daudon et al., 2009), COD (Tazzoli and Domeneghetti, 1980) and COT (Basso et al., 1997) structures were relaxed at DFT level. The unit cell parameters and the atomic positions were optimized, as previously described for COM (Colas et al., 2013). The Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) was used (Kresse and Hafner, 1993, 1994; Kresse and Furthmüller, 1996). The corresponding crystallographic information files (CIFs) are available upon request.

This study has demonstrated that the solid-state NMR technique offers a complementary characterization approach for the study of kidney stones and related synthetic model systems. The 1H DUMBO MAS NMR technique provides unambiguous identification of the different calcium oxalate hydrate phases. This experiment is a rapid-measurement technique which can be easily adapted to yield semi-quantitative data. For the first time, the natural abundance 43Ca MAS NMR data from the three calcium oxalate hydrate phases have been presented together; these data exhibited sufficient signal to noise to facilitate a complete structural interpretation in agreement with crystallographic data. The extension of this approach to the study of KSs was attempted, showing that a real signal could be measured but with relatively limited discrimination between the different KSs samples. The deconvolution of the 1H and 13C MAS NMR data into assigned subspectra aided the interpretation of the data describing the whole system, thus demonstrating that KSs materials are usually a complex association of organic and inorganic components. Additional 31P MAS NMR studies provided further insight into the composition of the low-level phosphates which are ubiquitous and difficult to characterize in KSs. The development of solid-state NMR, in combination with modern computational DFT and machine learning approaches, would be able to characterize the complex heterogeneous biomaterials such as KSs without ambiguity (Tielens et al., 2021). As part of on-going studies building on the observations here, systematic NMR studies of a large range of KSs from the Tenon Hospital's collection is being undertaken to develop new diagnosis NMR approaches that could impact on developing novel treatments.

Figure A1FTIR spectra of two KSs containing a mixture of COM and COD phases. The main difference lies in the light blue wave number region corresponding to phosphate vibrations (913, 961, 1090 cm−1 hydroxyapatite; 870 cm−1 carbonates).

Figure A21H−13C CP DNP HETCOR MAS NMR spectrum of COM at T=100 K. In total, four distinct 1H resonances are clearly evidenced on the 1H indirect dimension. The contact time is 9.0 ms, and 16 correlations are observed. Note: the temperature used (100 K) has an impact on the values of the 13C chemical shifts. The main goal here is to demonstrate that four 1H resonances are clearly observed in the indirect dimension.

Figure A313C CP MAS NMR spectra of all KSs presented in this work (700 MHz). The contact time in milliseconds is indicated systematically.

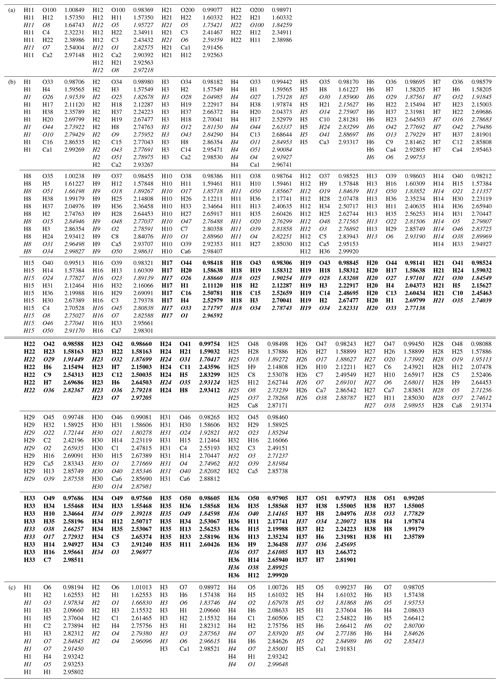

Table A1All CIFs are available upon request for COM, COD and COT. (a) Selected distances and the number of H…O contacts with Å (italic) for COM. The atomic positions were optimized at the DFT level. (b) Selected distances and the number of H…O contacts with Å (italic) for COD. The atomic positions were optimized at the DFT level. In order to take into account the distribution of the zeolitic water molecules, a model corresponding to was first calculated (see below), i.e., Ca8C16O32(H2O)16(H2O)3. The less rigid molecules are highlighted in bold. The first four molecules are structural. The last three molecules are zeolitic. (c) Selected distances and the number of H…O contacts with Å (bold italic) for COT. The atomic positions were optimized at the DFT level.

All the data are shown in all the figures of the paper. The CIFs of COM, COD and COT structures are available upon request from the corresponding author.

CL performed all syntheses and recorded most of the NMR spectra in strong collaboration with CB, DL and DI. CG and FT performed all DFT optimizations. FB and LB-C were deeply involved in the interpretation of the NMR spectra, with the help of MES and JVH. MD, EL and DB provided the KS sample and interpreted the data as both physicians and a physical chemist, respectively. CB wrote the article, with the support of the coauthors.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the special issue “Geoffrey Bodenhausen Festschrift”. It is not associated with a conference.

DFT calculations were performed using HPC resources from GENCI-IDRIS (grant no. 097535). The UK 850 MHz solid-state NMR facility used in this research was funded by EPSRC and BBSRC (grant no. PR140003) and the University of Warwick, including funding, in part, from the Birmingham Science City Advanced Materials Projects 1 and 2 supported by Advantage West Midlands (AWM) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

This article is dedicated to Geoffrey Bodenhausen on the occasion of his 70th birthday.

This research has been supported by an École Doctorale (ED 397) doctoral fellowship of Sorbonne University.

This paper was edited by Perunthiruthy Madhu and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bak, M., Thomsen, J. K., Jakobsen, H. J., Petersen, S. E., Petersen, T. E., and Nielsen, N. C.: Solid-state 13C and 31P NMR analysis of urinary stones, J. Urol., 164, 856–863, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67327-2, 2000.

Basso, R., Lucchetti, G., Zefiro, L., and Palenzona, A.: Caoxite, Ca(H2O)3 (C2O4), a new mineral from the Cherchiara mine, northern Apennines, Italy, Neues Jb. Miner. Monat., 2, 84–96, https://doi.org/10.1127/njmm/1997/1997/84, 1997.

Bazin, D., Daudon, M., Combes, C., and Rey, C.: Characterization and some physicochemical aspects of pathological microcalcifications, Chem. Rev., 112, 5092–5120, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr200068d, 2012.

Bazin, D., Haymann, J.-P., and Letavernier, E.: From urolithiasis to pathological calcification: a journey at the interface between physics, chemistry and medicine. A tribute to Michel Daudon, C.R. Chim., 19, 1388, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2016.10.001, 2016.

Bazin, D., Letavernier, E., Haymann, J.-P., Frochot, V., and Daudon, M.: Crystalline pathologies in the human body: first steps of pathogenesis, Ann. Biol. Clin.-Paris, 78, 349–362, https://doi.org/10.1684/abc.2020.1557, 2020.

Bowers, G. M. and Kirkpatrick, R. J.: Natural abundance 43Ca NMR as a tool for exploring calcium biomineralization: renal stone formation and growth, Cryst. Growth Des., 11, 5188–5191, https://doi.org/10.1021/cg201227f, 2011.

Butusov, M. and Jernelöv, A.: Phosphorus in the organic life: cells, tissues, organisms, in: Phosphorus. SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science, vol 9., Springer, New York, NY, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6803-5_2, 2013.

Cavanagh, J., Fairbrother, W. J., Palmer III, A. G., and Skelton, N. J.: Protein NMR spectroscopy, principles and practice, 2nd edn., Academic Press, Burlington, MA, USA, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-164491-8.X5000-3, 2007.

Colas, H., Bonhomme-Coury, L., Diogo-Coelho, C., Tielens, F., Babonneau, F., Gervais, C., Bazin, D., Laurencin, D., Smith, M. E., Hanna, J. V., Daudon, M., and Bonhomme, C.: Whewellite, : structural study by a combined NMR, crystallography and modelling approach, CrystEngComm, 15, 8840–8847, https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CE41201F, 2013.

Daudon, M., Bazin, D., André, G., Jungers, P., Cousson, A., Chevallier, P., Veron, E., and Matzen, G.: Examination of whewellite kidney stones by scanning electron microscopy and powder neutron diffraction techniques, J. Appl. Cryst., 42, 109–115, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889808041277, 2009.

Dazem, C. L. F., Amombo Noa, F. M., Nenwa, J., and Öhtström, L.: Natural ans synthetic metal oxalates – a topology approach, CrystEngComm, 21, 6156–6164, https://doi.org/10.1039/c9ce01187k, 2019.

Deganello, S.: The structure of whewellite, CaC2O4⋅H2O at 328 K, Acta Crystallogr. B, 37, 826–829, https://doi.org/10.1107/S056774088100441X, 1981.

Dessombz, A., Coulibaly, G., Kirakoya, B., Ouedraogo, R. W., Lengani, A., Rouzière, S., Weil, R., Picaut, L., Bonhomme, C., Babonneau, F., Bazin, D., and Daudon, M.: Structural elucidation of silica present in kidney stones coming from Burkina Faso, C.R. Chim., 19, 1573–1579, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2016.06.012, 2016.

Eckert, H., Yesinowski, J. P., Silver, L. A., and Stolper, E. M.: Water in silicate glasses: quantitation and structural studies by proton solid echo and magic angle spinning NMR methods, J. Phys. Chem., 92, 2055–2064, https://doi.org/10.1021/j100318a070, 1988.

Feike, M., Demco, D. E., Graf, R., Gottwald, J., Hafner, S., and Spiess, H. W.: Broadband multiple-quantum NMR spectroscopy, J. Magn. Reson. A, 122, 214–221, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmra.1996.0197, 1996.

Gan, Z., Hung, I., Wang, X., Paulino, J., Wu, G., Litvak, I. M., Gor'kov, P. L., Brey, W. W., Lendi, P., Schiano, J. L., Bird, M. D., Dixon, I. R., Toth, J., Boebinger, G. S., and Cross, T. A.: NMR spectroscopy up to 35.2 T using a series-connected hybrid magnet, J. Magn. Reson., 284, 125–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2017.08.007, 2017.

Gardner, L. J., Walling, S. A., Lawson, S. M., Sun, S., Bernal, S. A., Corkhill, C. L., Provis, J. L., Apperley, D. C., Iuga, D., Hanna, J. V., and Hyatt, N. C.: Characterization of and structural insight into struvite-K, MgKPO4⋅6H2O, an analogue of struvite, Inorg. Chem., 60, 195–205, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02802, 2021.

Gay, C., Letavernier, E., Verpont, M.-C., Walls, M., Bazin, D., Daudon, M., Nassif, N., Stéphan, O., and De Frutos, M: Nanoscale analysis of Randall's plaques by electron energy loss spectromicroscopy: insight in early biomineral formation in human kidney, ACS Nano, 14, 1823–1836, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b07664, 2020.

Gehl, A., Dietzsch, M., Mondeshki, M., Bach, S., Häger, T., Panthöfer, M., Barton, B., Kolb, U., and Tremel, W.: Anhydrous amorphous calcium oxalate nanoparticles from ionic liquids: stable crystallization intermediates in the formation of whewellite, Chem. Eur. J., 21, 18192–18201, https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201502229, 2015.

Gervais, C., Laurencin, D., Wong, A., Pourpoint, F., Labram, J., Woodward, B., Howes, A. P., Pike, K. J., Dupree, R., Mauri, F., Bonhomme, C., and Smith, M. E.: New perspectives on calcium environments in inorganic materials containing calcium–oxygen bonds: a combined computational–experimental 43Ca NMR approach, Chem. Phys. Lett., 464, 42–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2008.09.004, 2008.

Godinot, C., Gaysinski, M. Thomas, O. P., Ferrier-Pagès, C., and Grover, R.: On the use of 31P NMR for the quantification of hydrosoluble phosphorus-containing compounds in coral hosts tissues and cultures zooxanthellae, Scientific Reports, 6, 21760, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21760, 2016.

Gopinath, T. and Veglia, G.: Probing membrane protein ground and conformationally excited states using dipolar- and J-coupling mediated MAS solid state NMR experiments, Methods, 148, 115–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.07.003, 2018.

Heijnen, W., Jellinghaus, W., and Klee, W. E.: Calcium oxalate trihydrate in urinary calculi, Urol. Res., 13, 281–283, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00262657, 1985.

Huskić, I., Pekov, I. V., Krivovichev, S. V., and Friščić, T.: Minerals with metal-organic framework structures, Sci. Adv., 2, e1600621, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600621, 2016.

Iuga, D., Schäfer, H., Verhagen, R., and Kentgens, A. P. M.: Populations and coherence transfer by double frequency sweeps in half-integer quadrupolar spin systems, J. Magn. Reson., 147, 192–209, https://doi.org/10.1006/jmre.2000.2192, 2000.

Izatulina, A. R., Gurzhiy, V. V., and Franck-Kamenetskaya, O. V.: Weddellite from renal stones: structure refinement and dependence of crystal chemical features on H2O content, Am. Mineral., 99, 2-7, https://doi.org/10.2138/am.2014.4536, 2014.

Jayalakshmi, K., Sonkar, K., Behari, A., Kapoor, V. K., and Sinha, N.: Solid state 13C NMR analysis of human gallstones from cancer and benign gall bladder diseases, Solid State Nucl. Mag., 36, 60–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssnmr.2009.06.001, 2009.

Kresse, G. and Furthmüller, J.: Efficiency of Ab-Initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set, Comp. Mater. Sci., 6, 15–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0, 1996.

Kresse, G. and Hafner, J.: Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals, Phys. Rev. B, 47, 558(R), https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558, 1993.

Kresse, G. and Hafner, J., Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium, Phys. Rev. B, 49, 14251, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.49.14251, 1994.

Laurencin, D. and Smith, M. E.: Development of 31P solid state NMR spectroscopy as a probe of local structure in inorganic and molecular materials, Prog. Nucl. Mag. Res. Sp., 68, 1–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnmrs.2012.05.001, 2013.

Laurencin, D., Li, Y., Duer, M. J., Iuga. D., Gervais, C., and Bonhomme, C.: A 31P NMR perspective on octacalcium phosphate and its hybrid derivatives, Magn. Reson. Chem., 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.5149, 2021.

Laurent, G., Gilles, P.-A., Woelffel, W., Barret-Vivin, V., Gouillart, E., and Bonhomme, C.: Denoising applied to spectroscopies – Part II: Decreasing computation time, Appl. Spectrosc. Rev., 55, 173–196, https://doi.org/10.1080/05704928.2018.1559851, 2020.

Leroy, C.: Oxalates de calcium et hydroxyapatite: des matériaux synthétiques et naturels étudiés par des techniques RMN et DNP, Chapter 1, PhD thesis, Pierre et Marie Curie University, Paris, France, available at: http://www.theses.fr/19753385X (last access: 10 December 2020), 2016 (in French).

Lesage, A., Sakellariou, D., Hediger, S., Eléna, B., Charmont, P., Steuernagel, S., and Emsley, L.: Experimental aspects of proton NMR spectroscopy in solids using phase-modulated homonuclear dipolar decoupling, J. Magn. Reson., 163, 105–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00104-6, 2003.

Li, Y., Reid, D. G., Bazin, D., Daudon, M., and Duer, M. J.: Solid state NMR of salivary calculi: proline-rich salivary proteins, citrate, polysaccharides, lipids and organic-mineral interactions, C.R. Chim., 19, 1665–1671, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2015.07.001, 2016.

Matlahov, I. and van der Wel, P. C. A.: Hidden motions and motion-induced invisibility: dynamics-based spectral editing in solid-state NMR, Methods, 148, 123–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2018.04.015, 2018.

Mroue, K. H., Xu, J., Zhu, P., Morris, M. D., and Ramamoorthy, A.: Selective detection and complete identification of triglycerides in cortical bone by high-resolution 1H MAS NMR spectroscopy, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 18, 18687–18691, https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CP03506J, 2016.

Paruzzo, F. M. and Emsley, L.: High-resolution 1H NMR of powdered solids by homonuclear decoupling, J. Magn. Reson., 309, 106598, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2019.106598, 2019.

Petit, I., Belletti, G. D., Debroise, T., Llansola-Portoles, M. J., Lucas, I. T., Leroy, C., Bonhomme, C., Bonhomme-Coury, L., Bazin, D., Letavernier, E., Haymann, J.-P., Frochot, V., Babonneau, F., Quaino, P., and Tielens, F.: Vibrational signatures of calcium oxalate polyhydrates, ChemistrySelect, 3, 8801–8812, https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.201801611, 2018.

Pourpoint, F., Gervais, C., Bonhomme-Coury, L., Azaïs, T., Coelho, C., Mauri, F., Alonso, B., Babonneau, F., and Bonhomme, C.: Calcium phosphates and hydroxyapatite: solid-state NMR experiments and first-principles calculations, Appl. Magn. Reson., 32, 435–457, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00723-007-0040-1, 2007.

Reid, D. G., Jackson, G. J., Duer, M. J., and Rodgers, A. L.: Apatite in kidney stones is a molecular composite with glycosaminoglycans and proteins; evidence from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy, and relevance to Randall's plaque pathogenesis and prophylaxis, J. Urology, 185, 725–730, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.075, 2011.

Reid, D. G., Duer, M. J., Jackson, G. E., Murray, R. C., Rodgers, A. L., and Shanahan, C. M.: Citrate occurs widely in healthy and pathological apatitic biomineral: mineralized articular cartilage and intimal atherosclerotic plaque and apatitic kidney stones, Calcified Tissue Int., 93, 253–260, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-013-9751-5, 2013.

Ren, J., Dimitrov, I., Sherry, A., and Malloy, C.: Composition of adipose tissue and marrow fat by 1H MR spectroscopy at 7 Tesla, J. Lipid Res., 49, 2055–2062, https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.D800010-JLR200, 2008.

Ruiz-Agudo, E. Burgos-Cara, A., Ruiz-Agudo, C., Ibanez-Velasco, A., Cölfen, H., and Rodriguez-Navarro, C.: A non-classical view on calcium oxalate precipitation and the role of citrate, Nat. Commun., 8, 768, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00756-5, 2017.

Samoson, A.: Qone: Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) Probes, available at: https://qoneamericas.com/mas-probes-magic-angle-spinning/ (last access: 10 February 2021), 2019.

Schmidt-Rohr, K. and Spiess, H. W.: Multidimensional solid-state NMR and polymers, Acad. Press, Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-21335-3, 1994.

Shepelenko, M., Feldman, Y., Leiserowitz, L., and Kronik, L.: Order and disorder in calcium oxalate monohydrate: insights from first-principles calculations, Cryst. Growth Des., 20, 858–865, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.cgd.9b01245, 2019.

Sherer, B. A., Chen, L., Kang, M., Shimotake, A. R., Wiener, S. V., Chi, T., Stoller, M. L., and Ho, S. P.: A continuum of mineralization from human renal pyramid to stones on stems, Acta Biomater., 71, 72–85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2018.01.040, 2018.

Smith, M. E.: Recent progress in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance of half-integer spin low-γ quadrupolar nuclei applied to inorganic materials, Magn. Reson. Chem., 1-44, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.5116, 2020.

Steiner, T.: The hydrogen bond in the solid state, Angew. Chem. Int. Edit., 41, 48–76, https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<48::AID-ANIE48>3.0.CO;2-U, 2002.

Tazzoli, V. and Domeneghetti, C.: The crystal structure of whewellite and weddellite: re-examination and comparison, Am. Mineral., 65, 327–334, 1980.

Tielens, F., Vekeman, J., Bazin, D., and Daudon, M.: Opportunities given by density functional theory in pathological calcifications, C.R. Chimie, 24, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.5802/crchim.78, 2021.

Wong, A., Howes, A. P., Dupree, R., and Smith, M. E.: Natural abundance Ca-43 study of calcium-containing organic solids: a model study for Ca-binding biomaterials, Chem. Phys. Lett., 427, 201–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2006.06.039, 2006.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Quick and reliable assignment of hydrated calcium oxalate and organic phases by 1H high-resolution solid-state NMR experiments

- Natural abundance 43Ca solid-state NMR experiments

- Back to 13C NMR: spectral edition and reconstruction of spectra

- The ubiquitous (but elusive) presence of phosphorus in KSs: 31P MAS and CP MAS experiments

- Syntheses of hydrated calcium oxalate, kidney stones samples and NMR methods

- Conclusions and perspectives

- Appendix A

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Special issue statement

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Quick and reliable assignment of hydrated calcium oxalate and organic phases by 1H high-resolution solid-state NMR experiments

- Natural abundance 43Ca solid-state NMR experiments

- Back to 13C NMR: spectral edition and reconstruction of spectra

- The ubiquitous (but elusive) presence of phosphorus in KSs: 31P MAS and CP MAS experiments

- Syntheses of hydrated calcium oxalate, kidney stones samples and NMR methods

- Conclusions and perspectives

- Appendix A

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Special issue statement

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References